This fake beach is a magnet for tourists—and peaceful endangered sharks

In the Canary Islands, endangered angelsharks and European tourists are attracted to the same habitat which, for once, isn’t bad for the wildlife.

This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Out in the Atlantic Ocean, roughly 100 kilometers off the northwest coast of Africa, lies an archipelago known as the Canary Islands, created millions of years ago by intense volcanic activity. The biggest and most populated island, Tenerife, rises from the deep-ocean floor to a series of peaks, one of which is the third-largest volcano in the world. Tenerife’s interior highlands are a moonscape, while its coastline of lava rock and sheer cliffs is pounded by surf. In contrast to most of the island’s stark geology, north of the island’s capital, Santa Cruz, is a long crescent-shaped beach of soft yellow sand, with groves of palm trees and a calm bay created by a long breakwater. This is Playa de las Teresitas, a magnet for northern European tourists craving winter sun.

But most of the people sunbathing on Teresitas are likely unaware of what lurks in the shallow waters lapping the shoreline. The bay—engineered and less than 10 kilometers from the Canaries’ second-largest city—is a surprising haven for pups of one of the world’s most critically endangered fish: the angelshark.

When the Spanish took control of the Canaries in the 1400s, they began cultivating cash crops: cochineal and sugar cane in the beginning, and later adding bananas, tomatoes, and other valuable commodities. For centuries, the islands’ economy thrived, but it was a fragile wealth. Over the years, livelihoods were threatened by cycles of crop disease, competition from cheaper markets, and lava flows that wiped out harvests and turned good agricultural land into barren terrain. In the 1950s, the boom in package tourism showed promise as a new cash crop. But while the islands had the sunshine, warm climate, and ease of access from Europe needed for this new industry, they were missing a vital element: picture-postcard sandy beaches.

Cue planners on Tenerife, who concocted an audacious plan to make over one of the island’s exposed lava-rock beaches. They chose a stretch of coastline close to Santa Cruz and expropriated the avocado farms and other smallholdings. Earthmovers leveled the foreshore and intertidal zone, and they constructed a breakwater over a kilometer long. And then, from the Western Sahara on Africa’s northwest coast, they shipped in the pièce de résistance: 240,000 tonnes of sand.

By 1973, this gargantuan project, environmentally questionable from today’s viewpoint, was complete. As anticipated, tourists arrived. Unanticipated was what their presence gave to one of the world’s most endangered fish species—visibility. Maybe angelsharks always gathered here, but until recently, no one really knew.

Along Playa de las Teresitas, rows and rows of tourists lounge on beach chairs under umbrellas or pad across soft sand to cool down in the water. The breeze creates tiny sapphire-tipped waves on the water’s surface, a magical cover for what lies beneath—an angelshark nursery.

Female angelsharks regularly migrate to these ideally sheltered waters to give birth to anywhere between eight and 25 live pups, who remain in the shallows for about a year. Feeding on cuttlefish and other small prey, they grow to around 50 centimeters, about the same length as a newborn baby. Then they disappear for years until they are mature. Where they go is a mystery.For centuries, angelsharks had been common along the Atlantic coast of North Africa and Europe, as well as the Mediterranean. The ancient Greeks fished them; Pliny the Elder described the use of their skin to polish wood and ivory. On the British Isles, they were called monkfish for their resemblance to a monk’s hooded robes. With the advent of industrial bottom trawling in the late 1800s, they were easily caught and became a common food fish. By the 1960s, aggressive fishing of angelsharks, coupled with their extremely low reproductive rate, led to a dramatic decline in their populations. Targeting them eventually became commercially unviable and the name monkfish was relegated to another species, the anglerfish.

But angelsharks were still by-catch in other fisheries, and by the early 1970s, as developers barged Saharan sand to Tenerife, the fish were pushed close to extinction in most parts of the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

In the European Union and the United Kingdom, it has become illegal to fish or retain angelsharks. If one is accidentally caught, fishers must return it alive to the sea. But the main threat to angelsharks remains the powerful bottom-trawling industry, which accounts for over 30 percent of fish landed in the European Union.

The story in the Canary Islands is slightly different. Michael Sealey, a marine biologist with the Angel Shark Project (ASP) in Tenerife, says that bottom trawling has never been as viable in the Canaries as in most of Europe and the Mediterranean. The seabed is mostly too deep, he explains, the underwater topography laced with jagged seamounts and reefs where fishing gear can get hung up. On top of that, the European Commission has halted all trawling in the Canaries since 2005.

But biologists only became aware about a decade ago that the Canaries host an angelshark population. Subsequently, in 2014, the Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Museum Koenig Bonn, and Zoological Society of London collaborated to establish ASP. The project’s goal: to gather data on critical habitats, movement patterns, and reproductive biology of angelsharks, and work with local communities and officials to protect the fish. Life history information is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies and protecting valuable, if improbable, habitat—like Playa de las Teresitas.

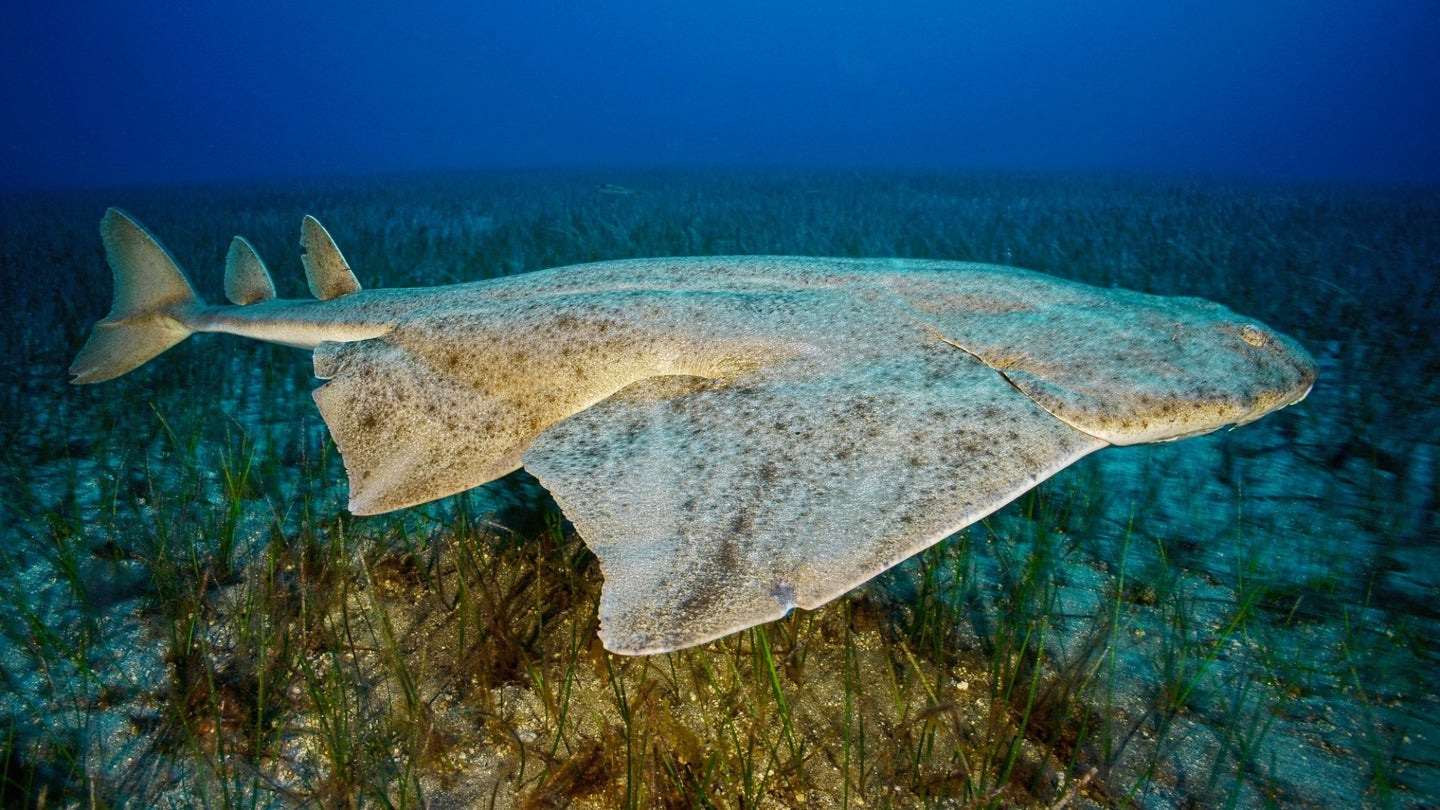

But angelsharks are not the easiest of research subjects. They are masters of disguise, so spotting them is a challenge. They have a peculiar flattened shape and spend most of their time lying on the ocean bottom partially covered by sand. Their coloring—reddish- or greenish-brown scattered with small white spots—helps them blend into the seabed.

Gathering data on such elusive animals, with low population densities spread over a huge area, is labor intensive. Help has come in the form of citizen science: everywhere in the Canary Islands, recreational divers and fishers are invited to make online reports of any sightings or accidental catches of angelsharks. Through an ASP initiative, dive operators conduct friendly competitions to see which company can record the most sightings, thereby increasing data collection, particularly from citizen scientists.

Rubén Martinez, a dive instructor in Lanzarote, the easternmost island of the Canaries, is a keen advocate of angelsharks and regularly volunteers for ASP surveys. He helps with procedures such as tagging the fish with either spaghetti tags—an easily attached plastic loop—or acoustic tags. Both are done on the spot without having to catch the fish or lift it out of the water. “We work in a team and practice beforehand,” Martinez says. After an angelshark has been spotted in the sand, the team places a mesh attached to a sturdy frame over the animal. They take a small sample of fin for DNA analysis and attach a tag to the base of the dorsal fin. The whole procedure, when done properly, takes less than a minute.

Surveys have shown that other beaches in the Canary Islands are also potential nursery sites. Interestingly, most of them have been altered, like Teresitas, to make them more attractive to people. On Lanzarote, Playa Chica boasts another long sweep of imported sand. It’s a magnet for divers—as well as a spectacular and easily accessible site—so the number of sightings of mature angelsharks off this shoreline is one of highest in the whole archipelago. How do the sharks react to these shoals of wetsuited humans? Alba Esteban Pacheco, a biologist and former dive instructor with Euro Divers Lanzarote, admits that while there have been instances of divers getting too close to the sharks, most dive companies are sensitive in this regard and brief their clients well. They have little choice: in 2019, Spain introduced legislation in the Canaries that made disturbing the sharks or harming their habitat and breeding grounds a criminal act subject to large fines.

Pacheco is very clear that she keeps her dive clients at least the recommended one meter distance from any angelsharks they find hiding in the sand. “Also,” she says, “these days, with everyone videoing everything and posting it on social media, it’s hard for divers to step out of line.”

But is this enough? Eva Meyers, a cofounder of ASP, acknowledges that the diving community plays a crucial role in conservation of the species. But she adds that much more needs to be done to ensure the long-term survival of angelsharks in areas like Playa Chica.

A recovery plan ASP developed with local authorities is in the final stages. It will include measures such as signage along sensitive coastlines and establishing a code of conduct for divers throughout the Canaries.

Among international dive communities, the word is out about the chance to see mature angelsharks in the Canaries, and this is a growing part of the tourism sector. Indeed, shark diving all over the world is a boon to economies. It generates over US $24-million yearly in the Canaries. Globally, shark-diving tourism generates over $300-million yearly, and local communities benefit much more from shark diving than from shark fishing. In some cases, this has led to the creation of marine reserves, such as in Fiji, which help other marine species as well.

Many divers may now be cognizant of the fragility of the angelshark population, but what about all those people splashing about and swimming in the all-important nursery areas just off the beaches? Sealey thinks that human activity in the shallow nursery areas influences angelshark behavior. On busy beaches like Teresitas, juveniles normally retreat to deeper water during the day when lots of people are around. During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions kept people off the beach. After almost two years of peace, angelsharks seemed unprepared for the people wading back into the water, as swimmers reported an unusual number of bites soon after restrictions lifted. The fish rely on their camouflage for protection, but when stepped on, they might lunge up from their hiding place and bite, though they usually swim away. Known locally as “gummings,” the bites are not serious and rarely draw blood. But the increase in gummings was an indication that the juveniles had adapted to remaining hidden in the shallows 24/7 to conserve energy. Post-pandemic, angelsharks have adapted again, by heading into deeper water earlier in the day and avoiding interactions with humans, as do many other urban wildlife species.

Back in the 1970s, did angelsharks also adapt to the Canaries’ headlong efforts to redesign itself for tourists? It’s intriguing to think that the massive, environmentally disruptive projects to remake beaches could have accidentally enhanced the habitat for one of the world’s rare fish species. But what’s clear is that after the breakwater was built and the sand arrived, people followed, and in the calm, shallow waters they began to see baby angelsharks. And unlike how many an association between humans and wildlife ends—in conflict and dead animals—this time it led to conservation.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.