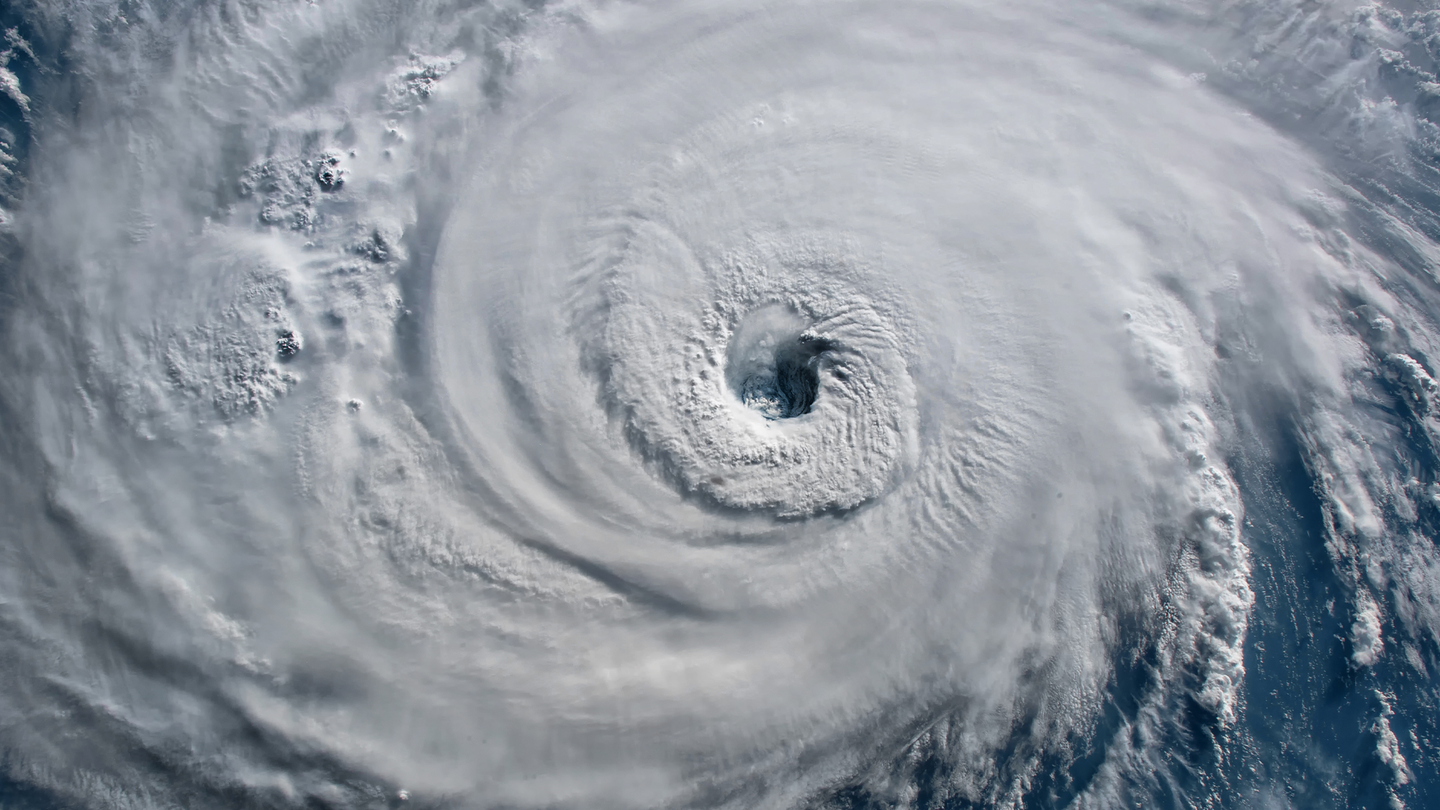

NOAA predicts a ‘near-normal’ Atlantic hurricane season for 2023

A looming El Niño and warm sea surface temperatures factor into this season’s unique forecast.

Atlantic hurricane season officially begins on June 1—and a disturbance in the Gulf of Mexico is already brewing. Tropical wave Invest 91-L only now has a 70 percent chance of becoming the first named system of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season—Arlene—but it will likely bring downpours and gusty thunderstorms to parts of Florida by the end of the work week whether or not it becomes a named storm.

[Related: What hurricane categories mean, and why we use them.]

For the 2023 season, NOAA forecasts a pretty average amount of hurricane activity. In their annual outlook, NOAA predicts a 40 percent chance of a “near-normal season”, a 30 percent chance of an “above-normal season”, and a 30 percent chance of a “below-normal season”.

The forecast calls for 12 to 17 total named storms—those with winds of 39 MPH or higher. NOAA anticipates that five to nine of these storms could become hurricanes (winds of 74 MPH or higher), including one to four major hurricanes. Major hurricanes are category 3, 4, or 5 storms with 111 MPH winds or higher.

Some of the names for this year’s storms include Cindy, Harold, and Sean among others.

The 2023 season is anticipated to be less active than recent years, partially due to a tug-of-war between some factors that suppress storm development and some that fuel it. This is the first year in three years without a La Niña pattern present, and the latest forecasts say there is a 90 percent likelihood that El Niño will develop by August and then remain strong in the fall.

El Niño’s influence on storm development may be offset by favorable conditions in the tropical Atlantic Basin. Those conditions include a potentially above-normal West African monsoon that helps create some of the Atlantic’s stronger and longer-lived storms, all while creating warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the Caribbean Sea and tropical Atlantic Ocean.

These warm waters are pure hurricane fuel, and those temperatures have been incredibly high this spring. But the temperatures in the North Atlantic basin, where the storms are born and intensify, and the eastern-central tropical Pacific Ocean, where El Niño forms, are the places to watch.

“This year, the two are in conflict—and likely to exert counteracting influences on the crucial conditions that can make or break an Atlantic hurricane season,” Iowa State University atmospheric scientist Christina Patricola writes in The Conversation. “The result could be good news for the Caribbean and Atlantic coasts: a near-average hurricane season. But forecasters are warning that that hurricane forecast hinges on El Niño panning out.”

[Related: El Niño is probably back—here’s what that means.]

Ocean temperatures in the Atlantic’s tropical regions were unusually warm during the most recent active hurricane seasons. In 2020, the Atlantic produced a record 30 named storms and the 2005 season produced 15 hurricanes including Hurricane Katrina.

The tropical Pacific Ocean influences the Atlantic hurricanes by forming teleconnections—a chain of processes that change the ocean or atmosphere in one region which then leads to larger scale changes that can influence the weather in other places.

“During El Niño events, the warm upper-ocean temperatures change the vertical and east-west atmospheric circulation in the tropics,” Patricola writes. “That initiates a teleconnection by affecting the east-west winds in the upper atmosphere throughout the tropics, ultimately resulting in stronger vertical wind shear in the Atlantic basin. That wind shear can tamp down hurricanes.”

Atlantic hurricane season ends on November 30. In the meantime, NOAA encourages those who could be affected by tropical systems to understand watches and warnings for their area and prepare emergency supplies ahead of time.