The US military wants ideas for fast aircraft that don’t need runways

DARPA is interested in new kinds of flying machines that are both speedy and capable of roughing it. Take a look at the designs they have in mind.

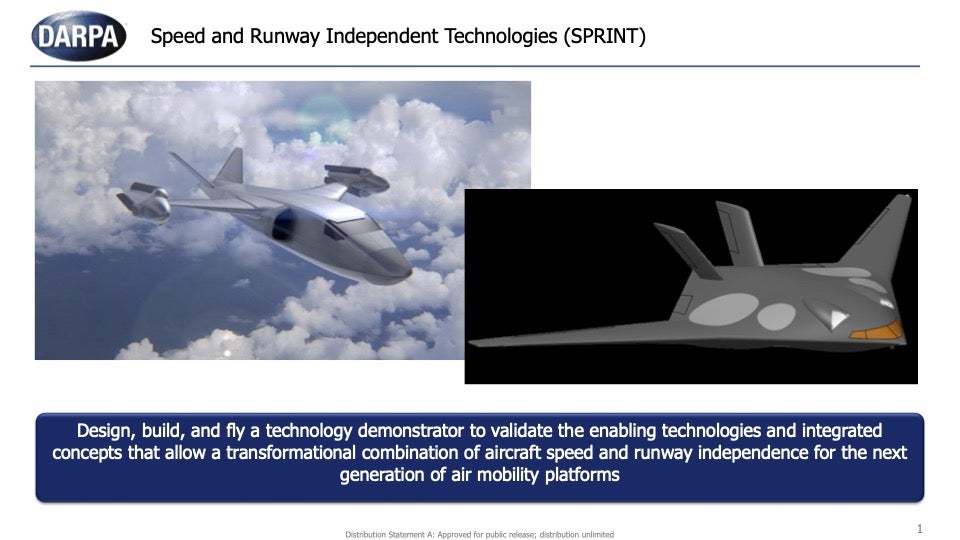

DARPA is inviting designers to reimagine aircraft that can fly fast and take off and land without runways. Earlier this month, DARPA announced an upcoming “Proposers Day,” to be held on March 23, when the Pentagon’s blue sky projects wing will offer information to designers and companies about an initiative it calls SPRINT, which stands for the SPeed and Runway INdependent Technologies (SPRINT) X-Plane Demonstrator program. In 42 months, or three and a half years, DARPA hopes to have a demonstration flight of a new plane through the program.

As the name suggests, SPRINT is looking for a fast aircraft, or at least a plane capable of going fast over short stretches. The program is specifically seeking to develop an aircraft that can cruise at 400 knots, or 460 mph. That’s well below the cruising speed of a fighter like the F-16, though it’s much faster than the cruising speed of Black Hawk helicopters, which might be the more relevant consideration. That’s because the other aspect of SPRINT is that the aircraft should be able to hover in austere environments, like fields or deserts, without the specific paved infrastructure of a runway or a helipad.

“The objective of the SPRINT program is to design, build, certify and fly an X-plane to demonstrate enabling technologies and integrated concepts necessary for a transformational combination of aircraft speed and runway independence for the next generation of air mobility platforms,” reads DARPA’s announcement.

While the open sky is vast, runways remain one of the more demanding parts of the infrastructure of flight. Once built, a runway is relatively easy to repair after an attack, provided no planes were destroyed at the time of incoming bombs and missiles. But clearing the space for a runway and hangars, as well as maintaining crew and planes, creates a durable target visible from space. As the United States war planners explore options should a war break out in the Pacific region, the known and fixed locations of existing runways could leave aircraft vulnerable to surprise attack. Even without the surprise, once planes are in the air, they will need a runway to land, and losing that surface can lead to, at best, harsh landings on unprepared ground, which damage the plane and risk the pilot.

[Related: Bell wants to soup up tilt-rotor aircraft by adding jet engines]

DARPA announced SPRINT on March 1. The shape of the new vehicle is undetermined, reported Patrick Tucker of Defense One. “It could be a new form of helicopter, or perhaps a vertical-takeoff-and-landing aircraft that might fly even faster.” Tucker also noted that the director of DARPA “deliberately avoided calling the program a vertical-lift effort, and an accompanying slide displayed two artist’s concepts that were decidedly unhelicopter-like.”

Helicopters, of course, have long been the most reliable form of vertical takeoff, though their design comes with major constraints on speed and efficiency. Matching the runway independence of a helicopter with the speed and endurance of fixed-wing flight is a problem the military has tried to solve for decades. The most successful variants have followed one of two paths. There’s tilt-rotor planes, like the V-22 Osprey and upcoming V-280 Valor, which have high-mounted wings, and rotors that pivot parallel to the ground to take off, before turning to a different angle for forward flight. The Osprey can land in austere environments, provided there is clearance for the rotors, though in normal conditions the planes are flown and landed at dedicated pads on military bases.

The other path, seen in the Harrier Jump Jet and the F-35B stealth fighter, uses ducted exhaust from a jet engine to lift the plane into the sky, before pivoting to forward thrust. This tremendous amount of heat and power have caused speculation, especially in the development of the F-35, that the engine would destroy all but the most specially prepared landing pads.

Neither of the designs shown by DARPA commit to these traditional Vertical Takeoff or Landing (VTOL) approaches. One, a silver-glossy image of a plane with jet-like ducts and folded blades on nacelles, has wings positioned like a tiltrotor. In the high-flight concept art, the engines used for vertical lift are drawn dormant, letting even more powerful systems propel the plane through the sky. The V-22 Osprey has a cruising speed of 310 knots, while the V-280 Valor has one just over 280 knots. Both planes have higher top speeds for, er, sprints, but getting to faster cruising speeds likely means ditching rotor engines as the primary form of propulsion, even if they can tilt.

In DARPA’s other concept drawing, the image appears as a rendering of a flying wing, reminiscent of the B-2 or B-21 bombers, but with a V-shaped tail. The engines are even more suggested than shown here, with space for ducted fans or rotors to provide vertical lift in the vehicle’s body, while jet intakes suggest means of forward propulsion.

Such concept art is a type of vision board for what DARPA is trying to accomplish. Getting a new kind of plane that can fly without runways, helipads, or other external infrastructure could expand where planes operate. Ensuring that the plane flies fast could make it useful for more tasks than those already performed by helicopters, expanding the scope of what the military might do. And, ultimately, DARPA’s mission is not to design finished products—it is to explore new spaces, trusting that once the hurdle of technological demonstration is accomplished, others will figure out how to bend that new technology into useful form.