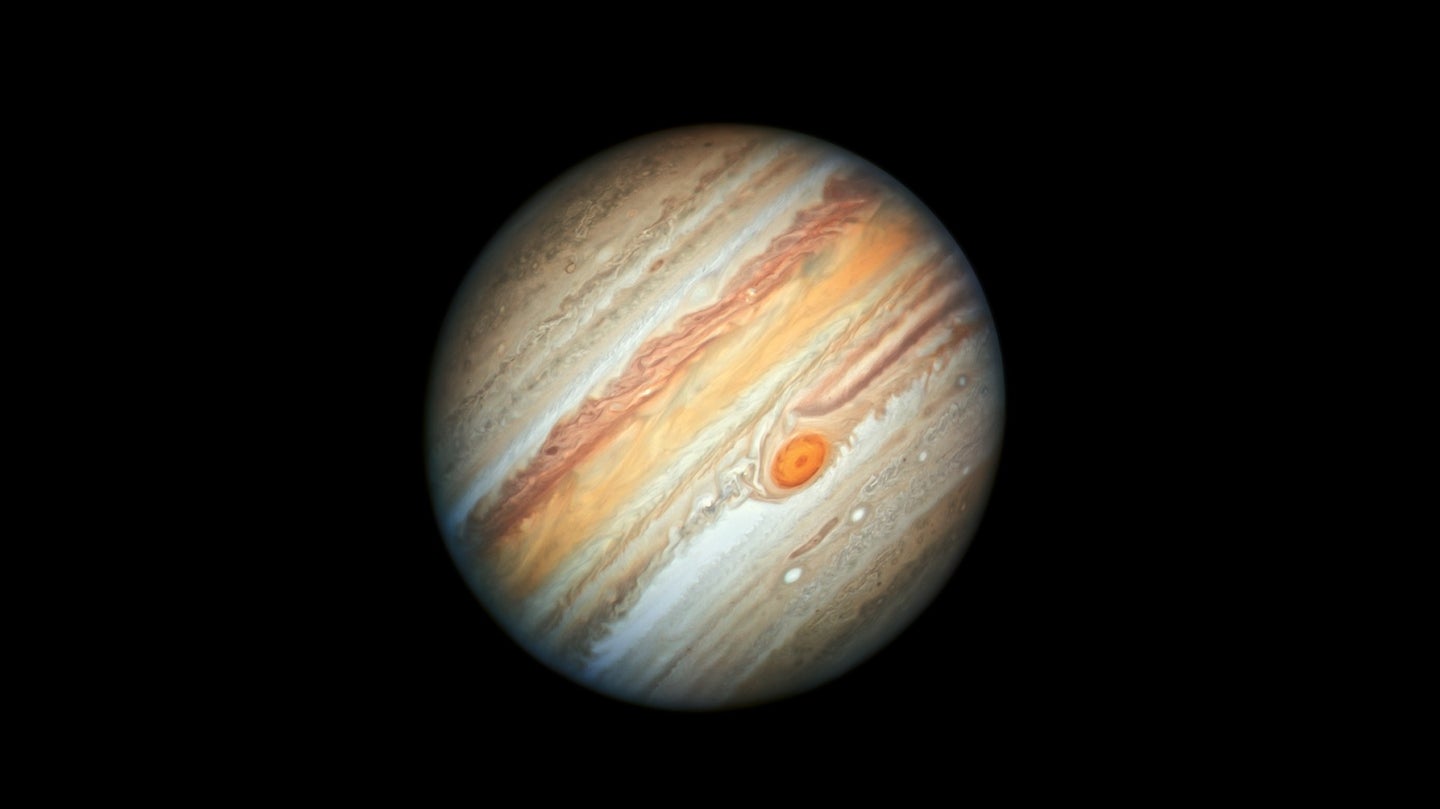

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is whirling faster than ever

Hubble has been observing the Jovian storm for more than a decade.

The famous Hubble Telescope keeps a watchful eye over many elements of space, including Jupiter and its stormy surface. After more than a decade of collecting data, NASA astronomers have discovered that the gas giant’s most famous storm, the Great Red Spot, is actually picking up wind speed.

Planetary scientists used Hubble data to observe the Great Red Spot on Jupiter between 2009 and 2020, capturing a full Jovian orbit around the sun. During that time, Hubble detected that the wind speeds on the outer edges of the storm picked up by 8 percent. Today, wind velocity can get up to 100 meters per second (that’s 223 mph or 360 kph)—whereas at the start of the study period, that measure was more typically in the low 90s. This increase was gradual and consistent over time, indicating that this trend might continue long term. In contrast, winds near the center of the storm actually slowed. The findings were published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“When I initially saw the results, I asked ‘Does this make sense?’ No one has ever seen this before,” Michael Wong, a planetary scientist at the University of California at Berkeley and lead author, said in a statement. “But this is something only Hubble can do. Hubble’s longevity and ongoing observations make this revelation possible.”

[Related: The Hubble Space Telescope just turned 30, and it’s working better than ever]

The Great Red Spot is a massive storm system—at about 10,000 miles across, it’s larger than Earth—and it’s been swirling for more than 190 years. It has been a point of astronomical wonder for human skygazers since the early 19th century, though it’s possible that it was sighted as early as the 1600s.

Scientists can more granularly study homegrown tempests with storm-chasing aircraft and Earth-orbiting satellites. But when a storm is on Jupiter, a telescope like Hubble is a better bet.

Still, while Hubble can glean a lot of information about the Jovian storm, it has its limitations. Hubble can’t get continuous storm wind speed readings on site, for example, nor can its instruments “see” anything below the top layer of the storm. So when it comes to how storm speed might be affecting Jupiter’s surface, that’s “hard to diagnose,” added Wong, because “anything below the cloud tops is invisible in the data.”

The changes in wind speeds are fairly small, amounting to an increase of less than 1.6 miles per hour per Earth year. But that makes the new finding all the more remarkable. Detecting such minute changes on a planet so far away in a storm so large is something astronomers could only do with Hubble and its long-lasting observations, said Amy Simon, a co-author of the new research and a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in the same statement. “We’re talking about such a small change that if you didn’t have 11 years of Hubble data, we wouldn’t know it happened,” she said. “With Hubble we have the precision we need to spot a trend.”

Astronomers will have to continue their observations to make out what these changes mean for Jupiter. Planetary scientists have previously determined that the Great Red Spot is also shrinking in size, getting taller, and becoming more circular in shape.