This fossilized butthole gives us a rare window into dinosaur sex

The cloaca is the hole-y grail to understanding prehistoric copulation.

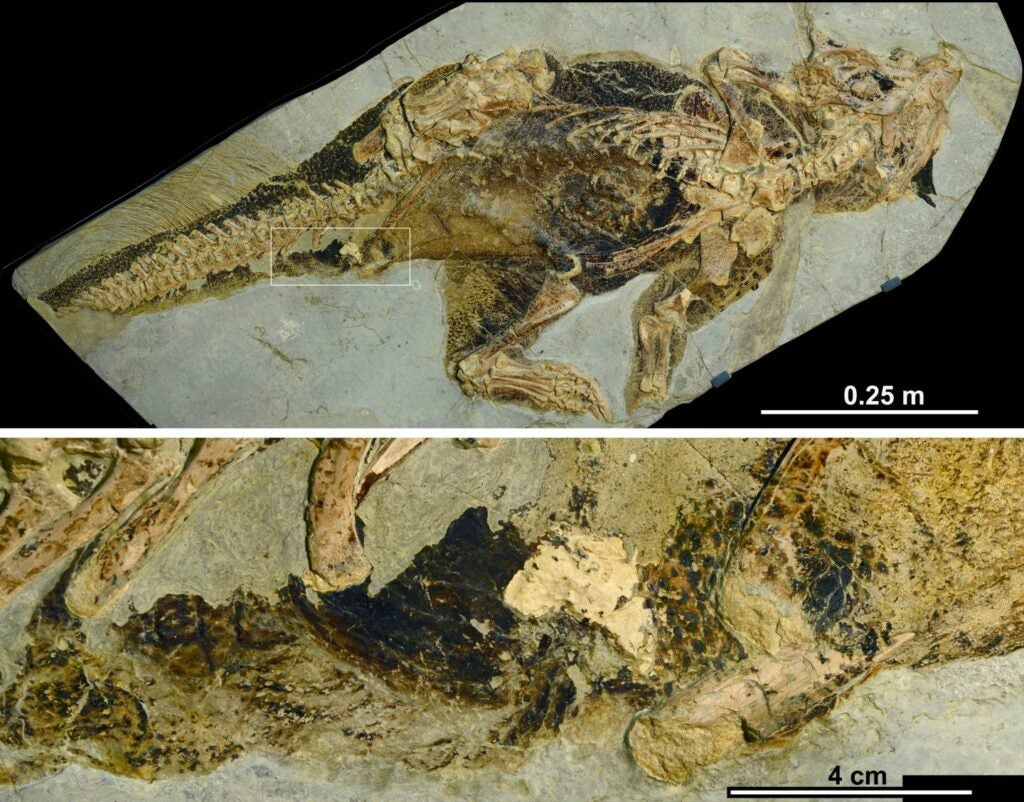

Dinosaur fossils can be, for lack of a better term, rather bare-bones—particularly in their delicate, easily-destroyed nether regions, which can fall prey to the ravages of scavengers, or an explosive release of postmortem gas. But after working with a dinosaur specimen from the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Germany, Jakob Vinther, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol, returned and realized that its private parts were unusually well-preserved.

“I was thinking, I wonder if anybody has ever found a dinosaur cloaca before?” he recalls.

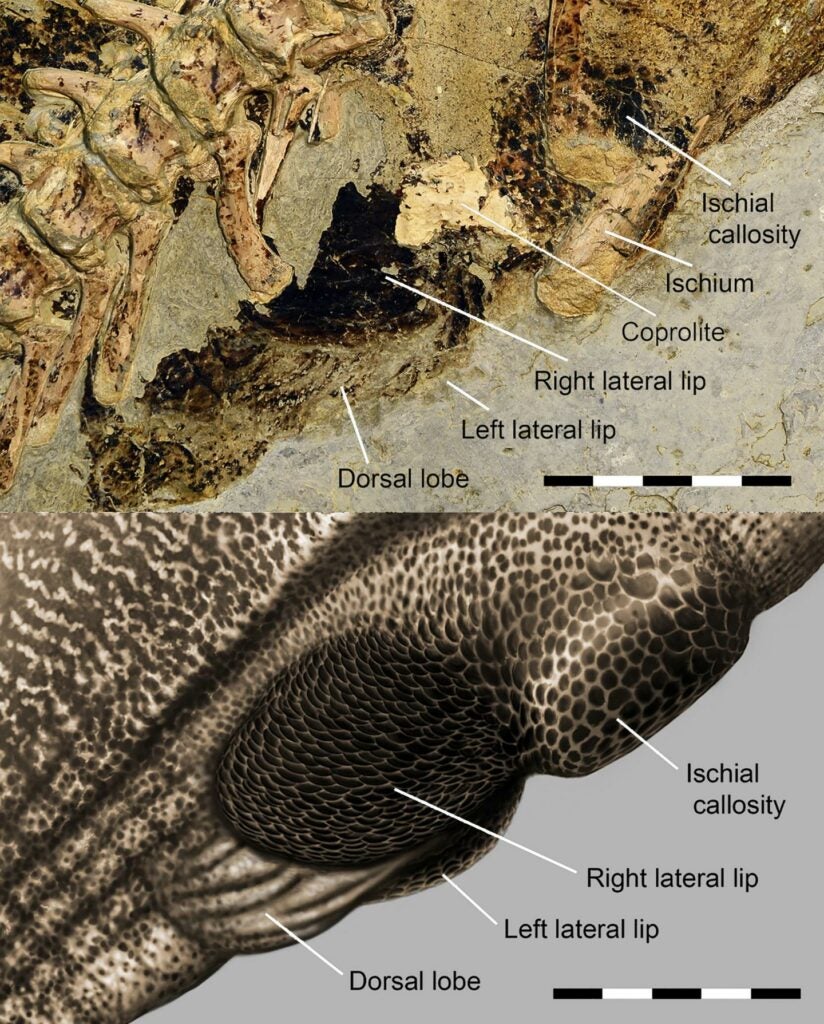

A cloaca, for those who aren’t familiar, is an opening common to non-mammalian (and a few mammalian) vertebrates that operates as a sort of one-size-fits-all funnel for sex, pooping, urination, and reproduction. In a study published yesterday in the journal Current Biology, Vinther and his colleagues, paleoartist Robert Nicholls and University of Massachusetts Amherst biologist Diane A. Kelly, were able to three-dimensionally reconstruct and describe what Vinther says is the only non-avian dinosaur cloaca known to be preserved.

Though it’s been described this way, a cloaca is “more than just a butthole,” says Vinther. “It’s the Swiss army knife of back ends.” For help with their description, Vinther says, the study authors looked to the wide-ranging cloaca of other land-dwelling vertebrates. Some, such as those belonging to turtles, look like a wizened, puckered grin. The cloaca of birds, our present-day dinosaurs, look “kind of like a cyst that needs to be popped,” Vintehr explains, while the cloaca of crocodile are covered in distinct scales, forming a sort of raised lobe with a slit in the middle.

The dinosaur owner of this particular cloaca is an approximately 120 million-year-old Psittacosaurus, hailing from what is now the Liaoning province in northeastern China. About the size of a labrador, the Psittacosaurus was surprisingly cute for a dinosaur, Vinther says, with scaly skin and horns on either side of its flat, E.T.-like face. The dinosaur’s cloaca appears to have a distinct color, which could have been used to signal for mates, as is sometimes the case for birds. It has a set of lips that join in a v-shape around a bean-like dorsal lobe, and contains what appears to be a coprolite, also known as fossilized poop (though the animal did not necessarily experience a dramatic mid-bowel-movement death, Vinther says; it could have emerged afterwards).

There are some similarities to the crocodile cloaca, co-author Diane Kelly—an expert in the evolution of copulatory systems—told the New York Times, and the study suggests that, like the crocodile, this dinosaur cloaca may have housed glands responsible for spewing out mate-attracting scents.

“The shape and color of the tissue that’s preserved suggests that these animals might have used both odor and visual signals to interact with other members of their species,” Kelly said in an email.

We’re only talking about one set of fossilized dinosaur privates, which limits the scope of any mate signalling takeaways, the study explains. But, though Vinther notes that these revelations aren’t “going to cure cancer, or prevent totalitarian people from entering political systems,” they do add a little piece to the puzzle of what life used to look like, which helps us understand why the living world looks the way it does today.

“Perhaps,” Vinther says, “there was a glorious past where dinosaurs were strutting around and showing their cloacas off.” One can only hope.