The mysterious ‘Tully monster’ didn’t have a spine after all

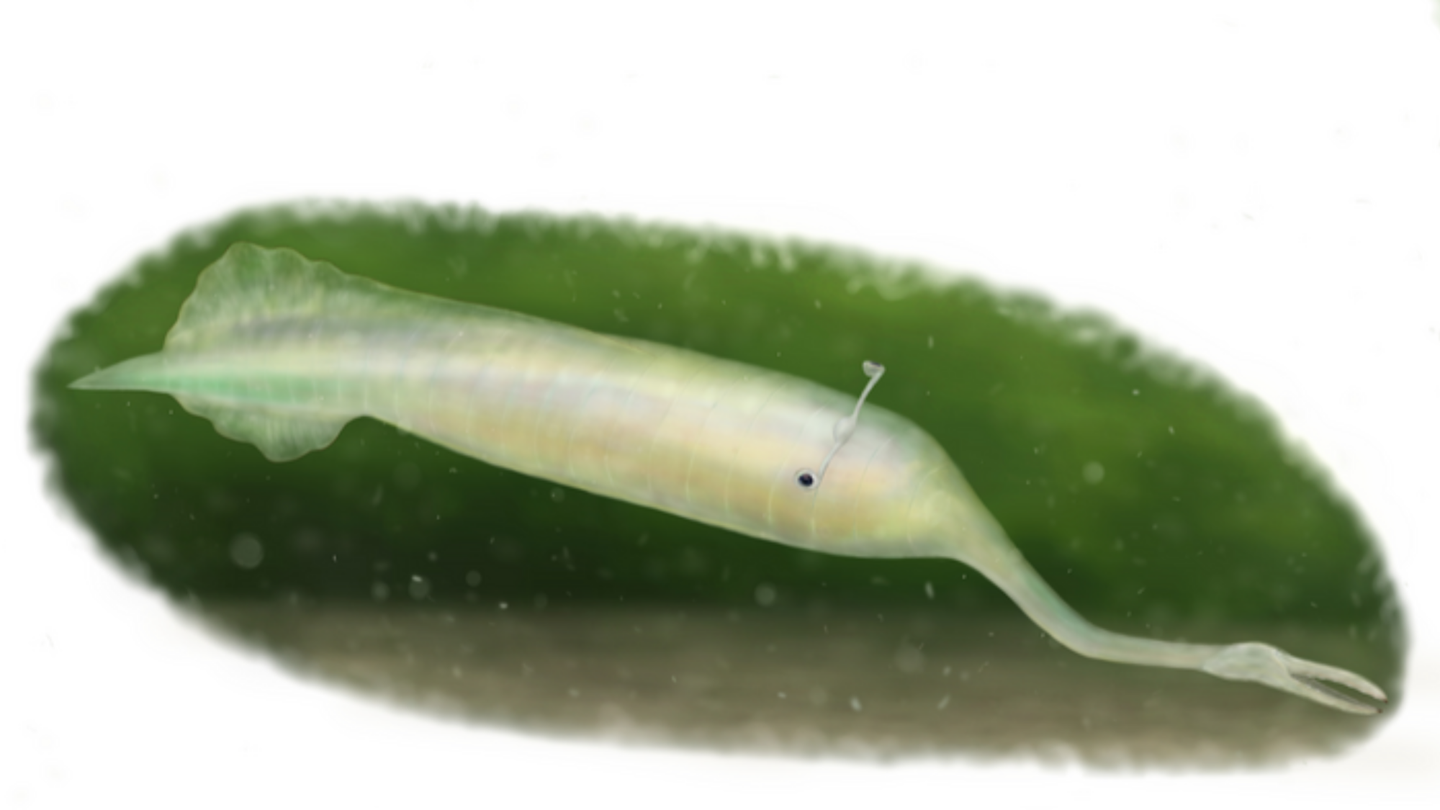

300 million years ago, this creature was swimming in the waters of modern-day Illinois.

Since its discovery nearly 70 years ago, paleontologists have debated the lineage of the mysterious “Tully monster.” The six-inch-long, stalk-eyed creature lived over 300 million years ago in the seas of modern-day Illinois. Its unique anatomy has long challenged researchers, making it difficult to identify as either a vertebrate or invertebrate–one of the first steps of classification.

Vertebrates are animals with spines, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Invertebrates are animals without spines, including insects, arachnids, crustaceans, mollusks, annelids, and more. The Tully monster, or Tullimonstrum gregarium, was a soft-bodied marine animal, so its fossilized remains do not show clear evidence of a backbone. In 2016, researchers claimed to have identified a pale gut-like structure as a notochord, a primitive spine, signaling a vertebrate affinity.

Now, researchers at the University of Tokyo believe they have solved the mystery of Tullimonstrum gregarium’s lineage, finding characteristics that point to an invertebrate identity. Their findings were published in the journal Palaeontology on April 17, 2023.

Amateur collector Francis Tully found the first fossils in Illinois’ Mazon Creek formation in 1955, a fossil bed known for its treasure trove from the Carboniferous period. He then took his unidentified ‘monster’ to the Field Museum of Natural History, where it confounded paleontologists and opened up a debate that would last decades. It was first described in a paper in 1966 and became the Illinois state fossil in 1989.

[Related: A gator-faced fish shaped like a torpedo stalked rivers 360 million years ago]

So far, researchers have been unable to determine whether the fossil was a vertebrate or invertebrate, one of the first bases of taxonomic identification. Invertebrates emerged first in the form of soft-bodied organisms, such as sponges, jellyfish, and worms over 600 million years ago. Vertebrates evolved after, during the Cambrian explosion about 540 million years ago. Both sides of the debate have evidence to support them, and it is still an open discussion. If found to be a vertebrate, the Tully monster would fill a gap in evolutionary history, connecting jawless fish (such as lampreys and hagfish) to jawed fish.

Recent findings suggest the opposite. Researchers at the University of Tokyo analyzed 3D imaging of 153 Tully monster fossils from Mazon Creek. They found structures that point to it being an invertebrate chordate, like a lancelet, a small eel-like marine invertebrate which evolved 500 million years ago. The Tully monster could also potentially be a radically modified protostome, a clade of animals encompassing insects and crustaceans, which first evolved around 540 million years ago along with vertebrates during the Cambrian explosion.

“The most important point is that the Tully monster had segmentation in its head region that extended from its body. This characteristic is not known in any vertebrate lineage, suggesting a nonvertebrate affinity,” Tomoyuki Mikami, a doctoral student in the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo at the time of the study and currently a researcher at the National Museum of Nature and Science, said in a press release.

The researchers found structures consistent with those of invertebrates, such as body segmentation, vertical tail fins and head shape. They also analyzed body parts thought to prove similar to those of vertebrates, such as a tri-lobed brain, tectal cartilage (supporting the eyes and optic nerves) and fin rays. They found that these structures, though similar, are not comparable to those of vertebrates.

[Related: One wormy Triassic fossil could fill a hole in the evolutionary story of amphibians]

Using three-dimensional imaging techniques, the authors described the morphology of the Tully monster’s proboscis and its stylets—thin, needle-like structures with a similar function as teeth, in depth. According to the research, these structures are inconsistent with the keratinous teeth found in lampreys and hagfish, two vertebrates thought to be distant relatives.

In one of the earliest studies on the unique animal published in 1969, researchers stated that “our conception of the diversity of the organic world is based upon a small sample consisting almost entirely of animals with preservable hard parts.” The Tully monster, however, has few of such parts—not unlike jellyfish and worms, which lack hard skeletal structures and leave only impressions in sediment as they are fossilized. Studying what little evidence we have of ancient soft creatures is crucial for reconstructing the history of life, as a significant number of Earth’s creatures became extinct without leaving any fossils behind.

“More and more research is needed to extract important clues from Mazon Creek fossils to understand the evolutionary history of life,” Mikami said.