Survivors of America’s first atomic bomb test want their place in history

The long road from Trinity to recognition

On April 1, 2017, the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico opened its Stallion gate to the public, like it does twice every year. For a few hours, visitors are free to wander the Trinity Test Site, where, on July 16, 1945, the United States tested the first atomic bomb in history, forever altering the destructive power available to humans. On the way in, the over 4,600 visitors were greeted by about two dozen protesters, whose signs bore a simple, stark message: The first victims of an atomic bomb are still living.

“I remember just like it happened yesterday,” said Darryl Gilmore, 89, then a student at the University of New Mexico, studying music and business courses. His brother had just returned from the war, and they needed to get him down to Fort Bliss in El Paso so he could process out. Gilmore borrowed the family car for the trip; he drove it back from Albuquerque to his parent’s home in Tularosa along Highway 380, which goes through Socorro and San Antonio and on to Carrizozo. It’s the same road people take to visit the Trinity site today. On that day in mid-July 1945, he stopped to check his tires, and then encountered a convoy of six army trucks.

“The lead driver, a sergeant, told me ‘put your windows up on your car, and drive out of here as fast as you can, there’s poison gas in the area,’” recalled Gilmore. “I found out much later that they were prepared to evacuate a bunch of ranch families in that neighborhood from miles around. I found out they didn’t evacuate anybody.”

“My folks had gotten up early that morning, before 5 o’clock, and they saw the flash from Tularosa, that explosion,” said Gilmore, “and of course in Albuquerque I didn’t notice it at all. The only thing that came out in the paper that afternoon was a statement that an ammunition dump in the remote corner of the range had exploded, and that’s all the information that was released at that time.”

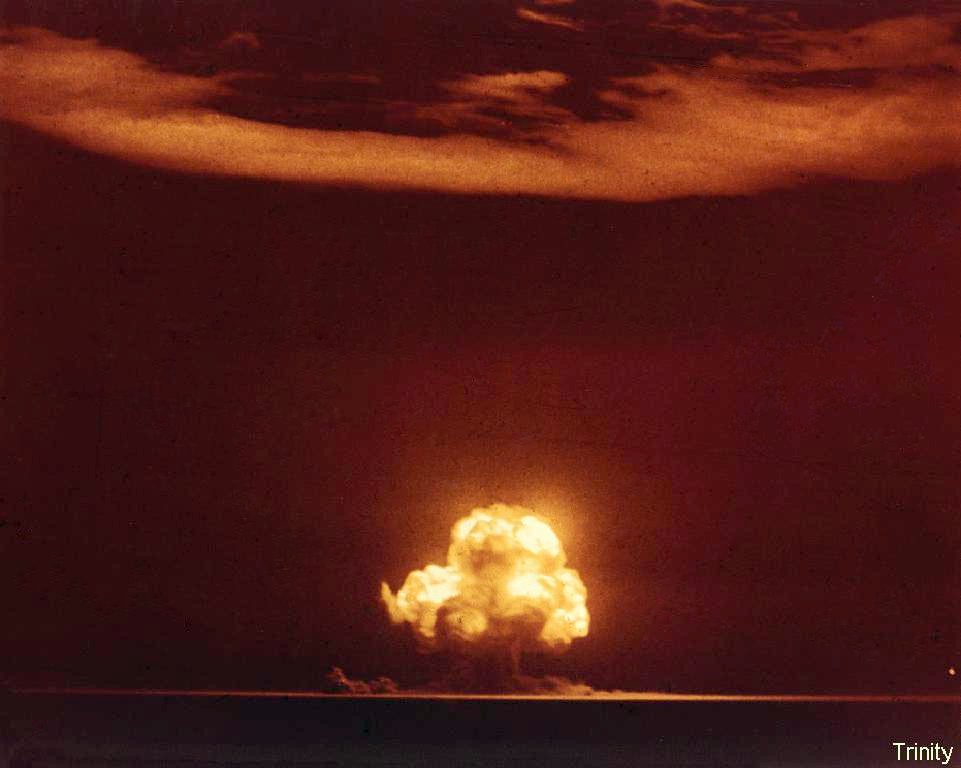

Color photograph of the Trinity Test

Apart from the convoy, and the statement about the ammunition dump, Gilmore didn’t hear any official word about what had happened in the New Mexico desert that day until shortly after the news that the A-bomb was dropped on Japan, first on Hiroshima on August 6,1945, and then on Nagasaki on August 9.

The effects of the fallout on Gilmore became clear much sooner than that. By the time he and his family reached El Paso, his arms, neck, and face were red—as if he’d gotten a bad sunburn. “I didn’t know at the time what had happened to me,” said Gilmore. “My outer skin gradually fell off the next few days, I used lotions and stuff on it, [but they] didn’t seem to make much difference. A few years later, I began to have skin problems, and I’ve had treatments ever since.”

Gilmore is the survivor of multiple cancers. His prostate cancer responded to radiation treatment and hasn’t returned, but his skin cancers remain a persistent problem to this day. And his immediate family—his father, mother, and sister—who were living in Tularosa at the time of the Trinity test, all died from cancer.

Gilmore’s story is one of many collected by the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. The organization was founded in 2005 by residents Tina Cordova and the late Fred Tyler, with the express aim of compiling information about the impacts of the Trinity test on people in the area. Tularosa is a village in Southern New Mexico, about a three-hour drive south of Albuquerque or a 90-minute drive northeast from Las Cruces. The town sits next to the White Sands Missile Range, and, as the crow flies, is about 50 miles from the Trinity Site. The White Sands Range summary of the 2017 visit says the site was selected because of its remote location, though the page also notes that when locals asked about the explosion, the test “was covered up with the story of an explosion at an ammunition dump.”

“Trinity Site,” a pamphlet available for visitors to the location, notes that it was selected from one of eight possible locations in California, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado in part because the land was already under the control of the federal government as part of the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, established in 1942. (Later, the Army tested captured V-2 rockets at the range, and today it houses everything from missile testing to a DARPA-designed Air Force observatory.) “The secluded Jornada del Muerto was perfect as it provided isolation for secrecy and safety, but was still close to Los Alamos for easy commuting back and forth,” notes the pamphlet.

Cordova disputes that characterization. “We know from the census data that there were 40,000 people living in the four counties surrounding Trinity at the time of the test,” she said. “That’s not remote and uninhabited.”

There is no mention in the pamphlet or the official online history page of any civilians in the area. The history contains an evacuation order report, filed July 18, 1945, detailing “plans to evacuate civilians around the Trinity Site area if high concentrations of radioactive fallout drifted off the Alamogordo Bombing Range.” From that report:

Immediately after the shot, the wind drift was ascertained to be sure the Base Camp was not in danger. Monitors were immediately sent out in the direction of the cloud drift to check the approximate width and degree of contamination of the area under the cloud. A small headquarters was set-up at Bingham, near the center of the area in the most immediate danger. The monitors worked in a wide area from this base reporting in to Mr. Hoffman or Mr. Herschfelter. One re-enforced [sic] platoon, under Captain Huene, was held at Bingham; the rest of the detachment was held in reserve at Base Camp. Fortunately no evacuations had to be made.

Gilmore’s experience suggests otherwise.

To this day, he’s surprised that there was no attempt by the Army or police to block off the roads in the area downwind of the test. “They should have known better,” said Gilmore. “That radiation spread for hundreds of miles, a lot of people in Tularosa died from cancer, and people in Tularosa attribute practically all of it to the A-bomb.”

Gilmore was driving from San Antonio to Carrizozo on highway 380, at about 9am on July 16, just hours after the Trinity test. It’s the same road that visitors take to get to the Trinity site today, and only 17 miles from the test location. Representation of Gilmore’s experience, or that of any civilians in the area at the time, are missing from the experience of the site itself.

On arrival, visitors first see the large rusting remains of “Jumbo,” a massive metal container built to catch rare and precious plutonium if the “Gadget,” the first atomic bomb, failed to work as planned. (Ultimately, confidence in Gadget was great enough that the planners decided not to use Jumbo, instead placing it 800 yards away from the blast site.)

Tourists pose inside “Jumbo”

The quarter-mile path from Jumbo to ground zero is fenced in, as is the blast site itself. It’s a simple chain link, with three strands of barbed wire angling outwards from the top, and intermittent “Caution: Radioactive Materials” signs placed on the outer edges of the fence. There is a small obelisk at the site, the official Ground Zero Monument, where crowds of tourists gather for their picture in the shallow depression of the first atomic blast. Facing the inside of the fence are a handful of small signs, printed up with photography of the site and observations about life in the area. Then there are a series of stills of the blast, captured milliseconds apart, showing the formation of the mushroom cloud. Finally, there is a flatbed truck with the casing from a Fatman bomb, the same kind dropped on Nagasaki. Tourists posed with the casing, asking strangers to take their picture in front of the weapon.

“Trinity Site is explicit about the story they’re trying to tell,” said Martin Pfeiffer, an Anthropology graduate student at the University of New Mexico focused on the social impacts of America’s nuclear enterprise. “The narrative is one of a new epoch, the atomic age, in which American technological and cultural might won World War II and, by implication, won the Cold War too. The Trinity Site is overtly triumphalist in their presentation of events and erases the experiences of those removed from the land without fair compensation or who may have suffered radiation injury.”

When asked about an official history of the site, officials with White Sands Missile Range directed me to “Trinity: The History Of An Atomic Bomb National Historic Landmark” by Jim Eckles, who worked in the White Sands Missile Range Public Affairs Office from 1977 to 2007.

“Other than a few instances, public exposure to radiation in the hours and few days after the 1945 test has largely been glossed over by officials and historians,” Eckles writes, and then says that may have changed after the 2010 publication of a study on Trinity as a source of public radiation exposure. Still, the possibility of a greater harmful impact in the area than initially reported can be seen as early as 1945, when the chief medical officer of the Manhattan Project recommended that future tests occur in a larger area “preferably with a radius of at least 150 miles without population.”

Part of the danger wasn’t just the immediate impact on people exposed to radiation the day of the blast, but also how the scattered fallout affected the people in the area.

“We have to remember what life was like in 1945 in rural New Mexico,” says the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium’s Cordova, “There were no water systems, so water was collected in cisterns and holding tanks, and that may have been contaminated after the bomb. There were no grocery stores. People bought things in a mercantile, things like flour, sugar, and coffee, but they didn’t buy meat, vegetables, food, anything that was perishable. They had orchards, they had gardens. People raised everything that they consumed meat-wise: cows goats, sheep, chickens. They hunted, and all of this was damaged. People didn’t bathe as often back then, because water was scarce, so it got on your skin and they were absorbing radiation. It did get into the water supply, and then they would consume it. It got into the food supply, then they would consume it. They would inhale the dust.”

Trinity test, 15 seconds after detonation

The secrecy around the project took the Army to some unusual places after the test and before the nature of the bomb became public.

“One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.” writes nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein. Indeed, we know that in December 1945, the Army purchased 75 head of cattle at market price from ranchers in the area, and proceeded to study the effects of radiation on those cows and their offspring. The area around Trinity, before it was fenced-off as a military gunnery range, was ranching country, with enough meager grass to support grazing herds. While the Army purchased some of the cattle affected by the blast, it’s highly likely that more cattle in the area at the time of the blast, or that grazed in the area after the blast, ended up consumed by locals. When cows consume radioisotopes of iodine that the blast deposited on grass, their digestive process accumulates isotopes from the whole grazed area; the cows can then pass the concentrated isotopes along through milk to humans.

This is echoed in testimony collected by Cordova on behalf of the Tularosa Downwinders. “We had this town hall meeting in Socorro when we had our report, and there were two sisters who came, and a brother, and they lived on a ranch that they said was 7-8 miles from Trinity, and said the government never paid them a visit, ever, and they said ‘our cows were wiped out; we ate them.'”

Historians of the Trinity test acknowledge that, after the blast, people in the area were largely left in the dark.

“No one did real medical and scientific follow-up with these ranchers,” writes Eckles. “For a couple years after the test, Los Alamos personnel discreetly inquired about the health of these folks without cluing them in on their concern.” This is a marked difference from how the United States treated the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. In October 1945, the United States set up a joint commission to study the long-term impact of the bomb on the lives of the people in the area. That study continues to this day, under the Radiation Effect Research Foundation, tracking and monitoring the health of people exposed to the blast.

Tourists read about Fatman, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki

Those populations are the largest and best-studied cohort of atomic survivors, but some of their experience doesn’t directly apply to those downwind of the Trinity test. The Trinity test’s low blast and scattered fallout is different than the atmospheric bursts over the Japanese cities, the climate of high desert is vastly different from coastal cities, and there is the matter of diet. Milk and cattle are a major part of life in rural New Mexico, in a way that simply was not true of people living in Japan.

The Downwinder’s report highlights this dietary exposure as one of the major harms from the blast to people in the area. In 2010, the Center for Disease Control published a draft report, the Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment, which looked at off-site health impacts from research done by the lab that designed and built the first atomic bombs. From the LAHDRA report:

All evaluations of public exposures from the Trinity blast that have been published to date have been incomplete in that they have not reflected the internal doses that were received by residents from intakes of airborne radioactivity and contaminated water and foods. Some unique characteristics of the Trinity event amplified the significance of those omissions. Because the Gadget was detonated so close to the ground, members of the public lived less than 20 mi downwind and were not relocated, terrain features and wind patterns caused “hot spots” of radioactive fallout, and lifestyles of local ranchers led to intakes of radioactivity via consumption of water, milk, and homegrown vegetables, it appears that internal radiation doses could have posed significant health risks for individuals exposed after the blast.

The recurring theme of studies about the impact of the Trinity test on people in the surrounding area is that there is a lack of thorough assessment of what actually happened—of what knowable, traceable harms from the bomb impacted people caught in its fallout. The National Cancer Institute plans to conduct one such study. Reached for this story, the NCI declined to comment, noting that the study is not yet in the field and therefore there are no results to report.

In lieu of a published federal study specifically on the health impact of the Trinity test, the Tularosa Downwinders themselves conducted a Health Impact Assessment with funding from the Santa Fe Community foundation. Some phrasings in the study misstate the science at hand. When the study says “We want to convey the fact that one millionth of a gram of plutonium inhaled or ingested into the body will cause cancer,” it states as certain fact that plutonium ingestion will cause cancer, rather than the more accurately describing plutonium ingestion as increasing the risk of developing cancer. To make the case for radiation exposure compensation, the Downwinder Consortium wants a study to happen soon, while the first generation is still around to testify to their experience of the blast. And they want to make sure that they’re consulted for the study, so that New Mexico’s victims of radiation exposure aren’t erased from history a second time.

There is already a program paying for people exposed to radiation risk from the tests in Nevada. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, passed in 1990 and amended in 2000, provides lump-sum compensation to uranium workers in 11 states, to “onsite participants in atmospheric nuclear tests”, and also to downwinders in three states: Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Senate Bill 197, sponsored by Senator Crapo of Idaho, would among other changes expand that coverage to include Trinity site downwinders. The bill is currently in the Judiciary committee with no hearing scheduled, though according to the office of Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley, that could always change.

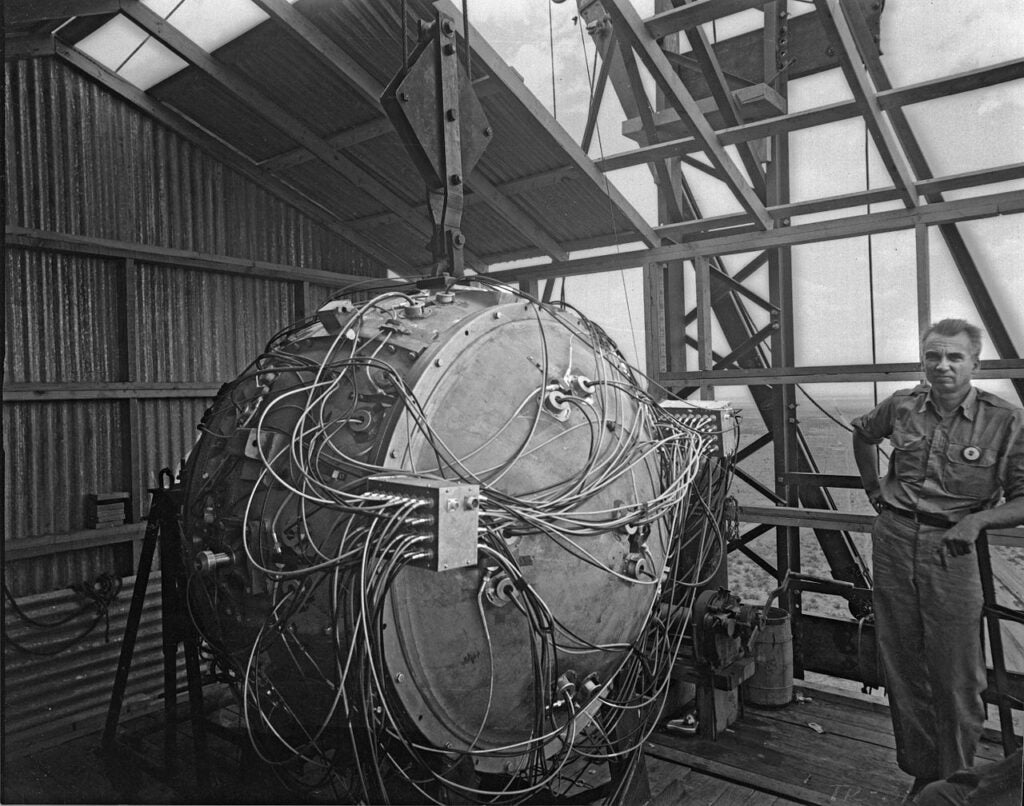

Gadget, the bomb tested at Trinity

“The Trinity test site was part of our war effort, used to defend our country and keep the American people safe. The federal government therefore has a solemn duty to compensate those injured as a result,” says Senator Tom Udall of New Mexico, one of the bill’s cosponsors. “I believe that the body of evidence shows a clear conclusion: people downwind of the Trinity test site were injured as a result of radioactive fallout, and downwind communities continue to suffer the consequences, both health and economic, of the Trinity testing. They should be compensated for their hardship.”

Compensation is a central goal of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium.

“I coined the phrase “unknowing, unwilling, and uncompensated,”” said Cordova, referring to the status of people impacted by the blast. “People who worked on the project were knowing, they knew what they were doing, they were willing to do it, and they were compensated at the time plus afterwards if they got sick. Those of us who gave no consent, never knew, were never willing, have never been taken care of.”

Compensation is just one part of the Downwinder’s request. “We want the government to come back and issue an apology to the people,” said Cordova. “That would go a long way in helping people to heal. There’s this trauma that’s been associated with this, that the government’s never going to come back and acknowledge it or take care of us.”

Gilmore is skeptical that an apology will ever happen. “I understand they made some settlements in Utah and Colorado, and Nevada, but nothing in the way that I know of in New Mexico, they just ignored New Mexico,” said Gilmore, “They’re just waiting for all us old people to die off so they don’t have to pay us any money for what happened to us.”

Part of the mission is to simply inform people that the downwinders exist. For five years, the Tularosa Downwinders have protested outside the road to the Stallion gate, a living addition to the story told through inanimate objects at Trinity itself.

“We decided, if people are going to go out there and celebrate the science,” said Cordova, “then we’re going to go out there, so that they know there were consequences too.”

Sign outside Trinity enclosure