How to test microphones and why you should

Learning how to test microphones properly starts every recording on the right note.

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Bad audio can ruin a project. If a podcaster’s voice-over is thin and reedy, it lacks authority. If a singer’s vocal track sounds like it was recorded through six inches of mud, it falls flat. These all-to-common scenarios are exactly why it’s important to test your microphones before a crucial session or performance. Microphones shape the sound they capture, and no two mics do it in exactly the same way. Testing them out not only ensures they’re in good working order, but it helps you understand a mic’s particular characteristics—its voice, if you will—so you can make sure it’s the right mic for the type of sound you’re after.

Manufacturers rely on high-end audio analyzers and special sound-deadening rooms called anechoic chambers to test and assess and chart every single subtle nuance of a microphone’s performance. While we certainly recommend you look into affordable ways to tune up your recording space, like soundproofing, you don’t need to go to complicated (and expensive) lengths to get a good take. Whether you’re a musician or singer, a home-recording engineer, a stage performer, or a videographer looking for the best audio, there are a number of techniques you can use to help learn how to test microphones and select the one that best suits the gig.

How to test microphones? Reading is fundamental

In order to make a, well, sound investment in a microphone you should start by reading different spec sheets to see what kind of performance the manufacturers claim you’ll get from their products. For instance, what are the mic’s polar patterns, frequency range, sensitivity? And what the heck do all those terms mean, anyway? Here are a few of the important things when it comes to how to test microphones.

Don’t be afraid to ask for directions

When people talk about types of mics, they first talk about the physical mechanisms inside them that convert sound into electrical impulses, which are dynamic vs condenser vs ribbon. There’s a lot of tech that could be shared about these types of capsules, but to give you a little quick guidance we’ll share a few things. A dynamic mic never needs to be powered, while condensers always do (and ribbons sometimes do). Dynamic mics (for example, the beyerdynamic M70 PRO X) have the warmest frequency response and are great for aggressive volumes, while condensers (like the Neat Microphones King Bee II) are the most extended and best for high-frequency precision when in more controlled situations. Ribbon mics, meanwhile, sit somewhere in the middle, are most fragile, but capture a distinct vintage vibe, a full room ambiance.

The next most important talking point is a microphone’s “polar” pattern. These patterns describe how mics respond to sound coming from different directions. For instance, a mic with an “omni” pattern picks up sound from all around it, making it great in the middle of an audience to record applause or general laughter. On the other hand, a “hypercardioid” mic, like a shotgun mic, is best with objects right in front of it, and a “supercardioid” mic does an even better job of rejecting sounds from the sides and rear. (Think boom operators on movie sets.) While a standard “cardioid” mic—like you see with singers on stage, TV reporters on location, podcasters at the coffee table, etc.—responds best to sounds right in front of it, but is much more forgiving with people who might not be perfectly positioned. Some mics are set up in a single pattern, while others feature microphone settings that include multiple selectable patterns.

So even before you test your mic you should test yourself. Do you have a clear idea of the subjects and situations you’ll be recording? The spaces you’ll have to set up in? Knowing that helps you have gear that can best capture your project.

Let your freq flag fly

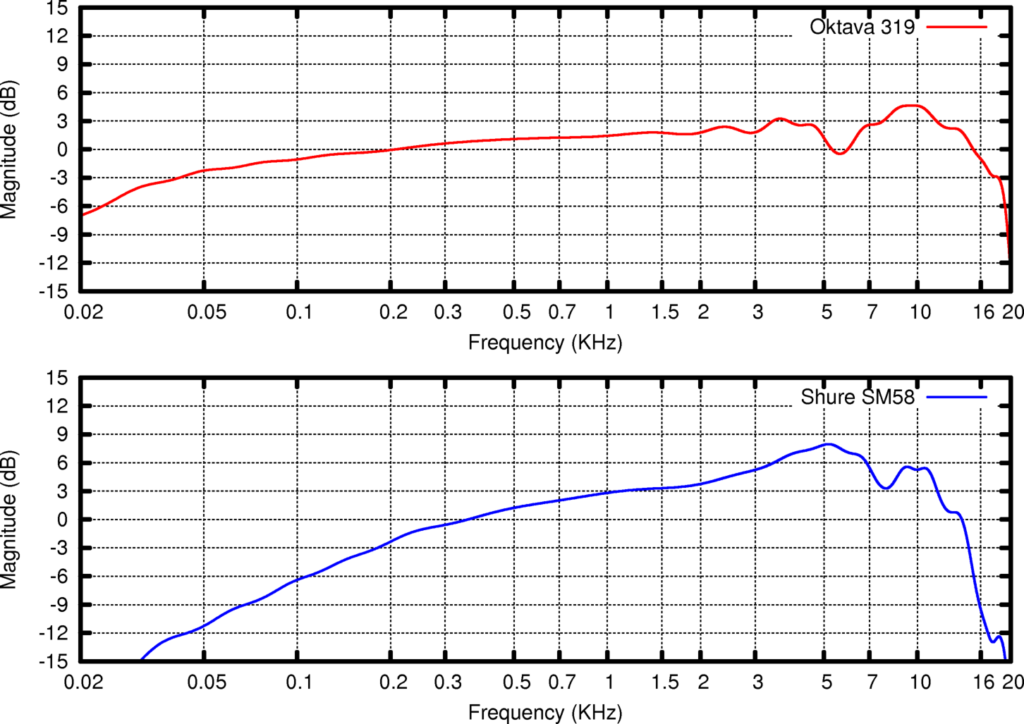

A sound’s pitch is determined by its frequency, or how fast the sound waves vibrate. Microphones are designed to capture certain frequencies better than others, and this is described as a mic’s frequency response. This is why the mic that might be great for vocals isn’t the best choice for kick drums (unless, of course, you’re making an intentional artistic decision to mess around with traditional miking techniques). Many microphones have a wide frequency response—often around 50 Hertz on the low end all the way up to 20,000 Hertz. That sounds like all mics might be great for any application. But a vocal mic, for instance, responds particularly well to core vocal frequencies of around 100 Hertz to 10 Kilohertz. Many also include a switch that rolls off frequencies around 20-80 Hz to help control low-end rumble. This isn’t the mic you’d want to put in front of a bass amp.

It pays to be sensitive

Sensitivity describes how well a microphone can convert pressure from sound waves into an electronic signal. In practical terms, you’d prefer a mic with a higher sensitivity for use in quieter situations. This way you can avoid boosting the gain and possibly adding unwanted noise to your signal. On the other hand, a mic with low sensitivity is perfect for when things get loud (like on stage with an amp that goes up to 11). Mic sensitivity is measured in decibels. The decibel (dB) scale is the basis for most mic specs, and it’s used to measure a microphone’s input sensitivity and its response to certain frequencies.

Testing … testing … mic check, mic check … sibilance sibilance

There’s no single, perfect microphone, and whether a mic is “good” for a job depends a lot on the type of sound you’re after. So before beginning, understand your goals. Will you be using it to mic an instrument? A flute, with its breathy, high-frequency notes, requires a different kind of mic than the one you’d stick in front of a beefy, growly guitar amp. Maybe you’re trying to capture elusive bird songs—or the in-your-face rumble of race cars at the Indy 500. You’ll want an extremely sensitive mic for those cardinals, and something that can handle a lot of input without distorting when you’re down on the track.

Don’t forget about where you’ll be using it. Recording in an acoustically controlled environment with a perfectly positioned mic is one thing. It’s an entirely different scenario when you’re trying to record your on-camera talent while they’re hanging by their fingernails from the side of a giant waterfall—you’ll never get the mic exactly where you want it and environmental noise is definitely a concern. A highly directional mic with a tight polar pattern and a low-frequency roll-off switch will help keep listeners focused on your outdoor adventurer.

That said, there are some universal goals when you do a microphone check that apply no matter where or how it’s used. You want your mic to capture all the frequencies that give your sound source nuance—if it’s the human voice, that means the highs that provide presence, the midrange “body,” and the lows that give it some weight and gravity. Your mic shouldn’t be so overly sensitive for its task that it distorts and ruins your recording. But it should be sensitive enough to capture your sound without needing to add too much gain, which can also ruin your recording with unwanted noise.

The manufacturer’s spec sheet can get you started, but you’ll still need to see if the microphone can deliver as promised. There are a number of tests you can easily perform without having to go into a fancy studio or engineering lab. They allow you to assess how a mic sounds under the best of circumstances, but also in situations that aren’t always ideal.

Just hit record

This is a mic test of how things sound when everything is just right. If you’re doing a sound test using vocals, set up the mic about a foot away from your singer and properly positioned for its polar pattern. Have your singer perform at different volumes, and try to choose a song with a pitch range of a couple octaves. If you’re running the microphone through a mixer, set the EQs to a neutral position, and turn any signal processing—including compressors and limiters—off. You don’t want to do anything that’ll color the sound unnecessarily. If possible, test the microphone on other sound sources, like musical instruments, tone generators, or even traffic noise if that’s something important to your final project. Oh, and don’t forget to invest in a trusty pair of studio monitors or mixing headphones, which are designed to have a flat response so that you can be assured you’re hearing the most accurate playback of what you’re recording. This will help you make those tiny, but much-needed mic adjustments. When it comes down to how to test microphones, a test take or two is a key component.

Go off your rocker

When the sound is coming from the optimal position for a microphone, it’s described as being “on-axis.” But it’s not always possible to position a microphone exactly where you want it, but it still has to capture the sound you’re after. On the other hand, maybe you’re conducting an interview on a noisy convention floor and you need a mic that only picks up whoever it’s pointed at. Either way, it’s important to understand how your mic performs with an off-axis sound source. Is it forgiving enough when you need it to be? Does it reject unwanted sounds when necessary? To perform this test, position the microphone about a foot from your source, but this time at a 45-degree angle. Listen for changes in frequency response, sensitivity, and overall clarity. How’s the sonic rejection? Turn on an air conditioner, or the TV, or a radio, and see how much of the noise bleeds into the mic while your main source is playing at the same time.

Get up close and personal

When I was in a punk band, I used to practically swallow my mic when I was singing on stage. Mostly, it just looked cool and that’s what we all did. It drove the guy behind the soundboard nuts because of something called the “proximity effect.” When a mic is too close to the singer, about an inch or so, it experiences a boost in bass frequencies. It can add a muddiness to the mix that some poor engineer needs to try EQing out—all because someone wanted to look like a badass. But not all mics respond the same way to this close proximity, so be sure to test yours by placing it close to your singer’s mouth while they belt out their tunes. (Coiling the cable around your wrist while stalking menacingly around the stage is optional.)

Handling noise

If you’re using a mic in a studio, chances are it’ll be attached to a stand using something called a shock mount that isolates it from vibrations or bumps. But on stage or on a reporting assignment, most people just hold the mic, and that can lead to all sorts of handling noise. Before you go in the field, gently tap the handle of the microphone, brush your fingers across the front, and try pulling it out of the mic stand’s clamp. How does it sound? The idea is to simulate and test the normal wear and tear a mic might experience at a gig or on a news assignment.

Proud to be loud … but silence is golden

Don’t forget to test a mic’s response to loud and soft noises. Put it in front of a blender and see if the sound distorts. Try whispering from a distance to see if it can hear you.

Crunch the numbers

Many brands of digital audio workstations (DAWs) and other music production software include scopes and meters to help analyze sound. These can show you a mic’s frequency response, its off-axis attenuation, and other helpful pieces of data. While they’re no substitute for careful listening, they can help you better understand what you’re hearing—or what you’re not hearing—when testing your microphone.

Try before you buy

It’s one thing to run tests in order to figure out how best to use the microphones you already own. But you can also test microphones to match your application before making a potentially expensive purchase—even when you don’t have access to a fancy recording studio. AV supply houses can be found in most cities, and many of them have a large selection of mics that you can rent for a few days. Some bigger specialty musical instruments or AV stores also sometimes rent equipment. If you have access to them, don’t be afraid to take some interesting mics for a test drive.

It’s possible you’ve used a microphone before that you really like—whether as a guest on someone else’s podcast or sitting in with a band during a recording session. Try renting one of those and then use it as a reference mic. For instance, I’m a documentarian and I love using the Sennheiser MKH50 as a boom mic. It’s wonderful for capturing the nuances of the human voice, and its supercardioid polar pattern excels at rejecting room noise. When I test out other boom mics, even when I’m trying out a compact shotgun mic such as the Sennheiser MKE 400, the MKH50 becomes my reference point and I always ask myself, “How does this new mic compare?” Now, say, you’re looking for the best podcasting mic for your situation and also happen to be in a band. There are plenty of choices, but you’d probably want to put them up against an established baseline such as the Shure SM7B, which has been a broadcasting reference mic for decades.

There are a few different ways to use a reference microphone. A human’s “audio memory” is only a few seconds long, so I rely on the A-B method of having both the new mic and reference mic capturing a signal at the same time, running them into their own channels on a small mixer, and then using the mute buttons (or just the faders) to alternate between listening to one or the other. If that’s not practical for some reason, I’ll set up the mics to each record to an individual channel for later playback—again using an A-B method to compare the two files.

When it comes to how to test microphones, practice makes perfect

A good quality microphone is an investment that can last a long time and carry you through many projects. In order to get the most out of your mic, you need to understand its strengths and weaknesses, which is why testing microphones is so important. But recording audio is as much art as science, and the real trick is learning how to use the information you pull from your tests to get the sound you want from your mic. So don’t forget to listen to what’s coming out of your recordings. Look at what the manufacturer’s documentation says the frequency response is, compare that to what you get from your own tests, but then use your ears to understand what a mic with that frequency response sounds like. Then go practice with it. Put it in front of different instruments, in the vocal booth, or out on the convention floor when you’re doing interviews. Listen to how it responds in each situation and then decide how best to use it. “Good” is a subjective term. You can’t tell if you really like something by reading numbers on a piece of paper. In the end, there’s no substitute for experience.