The number of colorectal cancer diagnoses has nearly doubled in people younger than 55, a recent report from the American Cancer Society (ACS) warns.

Colon cancer cases rose across the country from 11 percent in 1995 to 20 percent in 2019 people younger than 55. There was an 8-percent jump in advanced cases across all ages since the mid-2000s. Most young people who were diagnosed had late-stage tumors.

While the statistics are alarming, it doesn’t come as a surprise to doctors in the field who’ve noticed a trend in younger patients over the past few years. “This data is confirmation of that clinical observation,” says Deborah Nagle, the chief of colon and rectal surgery at Stony Brook Medicine in New York.

Colonoscopies remain the gold standard for screening colorectal cancer. However, some might find the preparation, recovery, and procedure itself uncomfortable and time-consuming. Fortunately, there are other less invasive tools for detecting colon cancer, some of which you can access in the comfort of your own home.

The reasons behind rising colon cancer rates

Why do some people get colon cancer over others? There’s “no smoking gun,” says Samir Gupta, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Several causes factor into an individual’s overall risk.

One is antibiotics: The drugs might contribute to colorectal cancer by changing the composition of the gut microbiome that allows “bad” bacteria—those that lower a person’s immunity, create cancer-promoting metabolites, and damage DNA—to flourish. A 2021 study in Sweden found adults treated with antibiotics had a 17 percent risk of cancer in the ascending colon. The more antibiotics people took, the greater the risk. Gupta says there could also be a potential link between antibiotic exposure during infancy and future colorectal cancer.

At 91 percent, colorectal cancer has one of the highest five-year survival rates.

Obesity is another contributor for different kinds of cancers, including early-stage colorectal. Nagle says the obesity rate has significantly increased in the US in the past few decades. Nearly 42 percent of Americans have a BMI of or above 30. Excess body fat promotes inflammation and drives up the production of insulin and hormones, and in turn, can increase the number of cells that can lead to cancer. Additionally, inflammation from fat itself sometimes damages healthy cells and leads to cancerous mutations in cellular DNA.

While less studied in humans, chemicals put in food have also been seen as a potential cancer contributor. Dietary emulsifiers, which are usually added to processed foods to increase their shelf life, have been linked to colon cancer through animal research. In one 2022 study, titanium dioxide, a common food coloring in candies and baking products, helped promote colorectal tumor development in lab mice.

[Related: Two decades-long studies link ultra-processed foods to cancer and premature death]

Oncology researchers are also interested in looking at how big of a role genetics play in colorectal cancer formation. One in five people diagnosed with colorectal cancer carry a genetic mutation associated with tumor development.

Prevention is possible, however. At 91 percent, colorectal cancer has one of the highest five-year survival rates. The key is catching it in time. Both Gupta and Nagle recommend getting a colonoscopy screening to detect any early signs of cancer. A follow-up study in Europe last year showed that people who got a colonoscopy reduced their risk of colorectal cancer by 31 percent and the risk of dying from said disease by 50 percent.

When to get a colonoscopy

While there are standard guidelines for when you should get a colonoscopy, both experts urge anyone who experiences persistent rectal bleeding and changes in bowel habits to get immediate medical attention.

If you have no symptoms and no family history of colorectal cancer, the ACS recommends routine screenings starting at age 45. Those considered at high risk of colorectal cancer—family history of disease, history of radiation in the abdomen area to treat prior cancer, inflammatory bowel syndrome—are encouraged to get a screening before 45.

People with Lynch syndrome, a hereditary condition that genetically predisposes a person to multiple types of cancer, are strongly urged to get a colonoscopy every one to two years starting in their early 20s or 2 to 5 years before the youngest case in the family.

Test your options

While colonoscopies are the go-to tool for colorectal screenings, says Nagle, they’re not all too popular among patients. The prep required for a colonoscopy—taking a laxative and adjusting your diet a few days before —can deter people. The procedure and recovery also takes up a huge chunk of time, which may not be doable for those who can’t take time off work.

Stool-based tests like Cologuard offer an easier, at-home alternative. There’s no prep needed, and the results are generally accurate, though not on par with a colonoscopy. There are also fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) that look for hidden blood in your stool. This annual test can be done at home, though it is less accurate at detecting polyps smaller than 6 millimeters than colonoscopies.

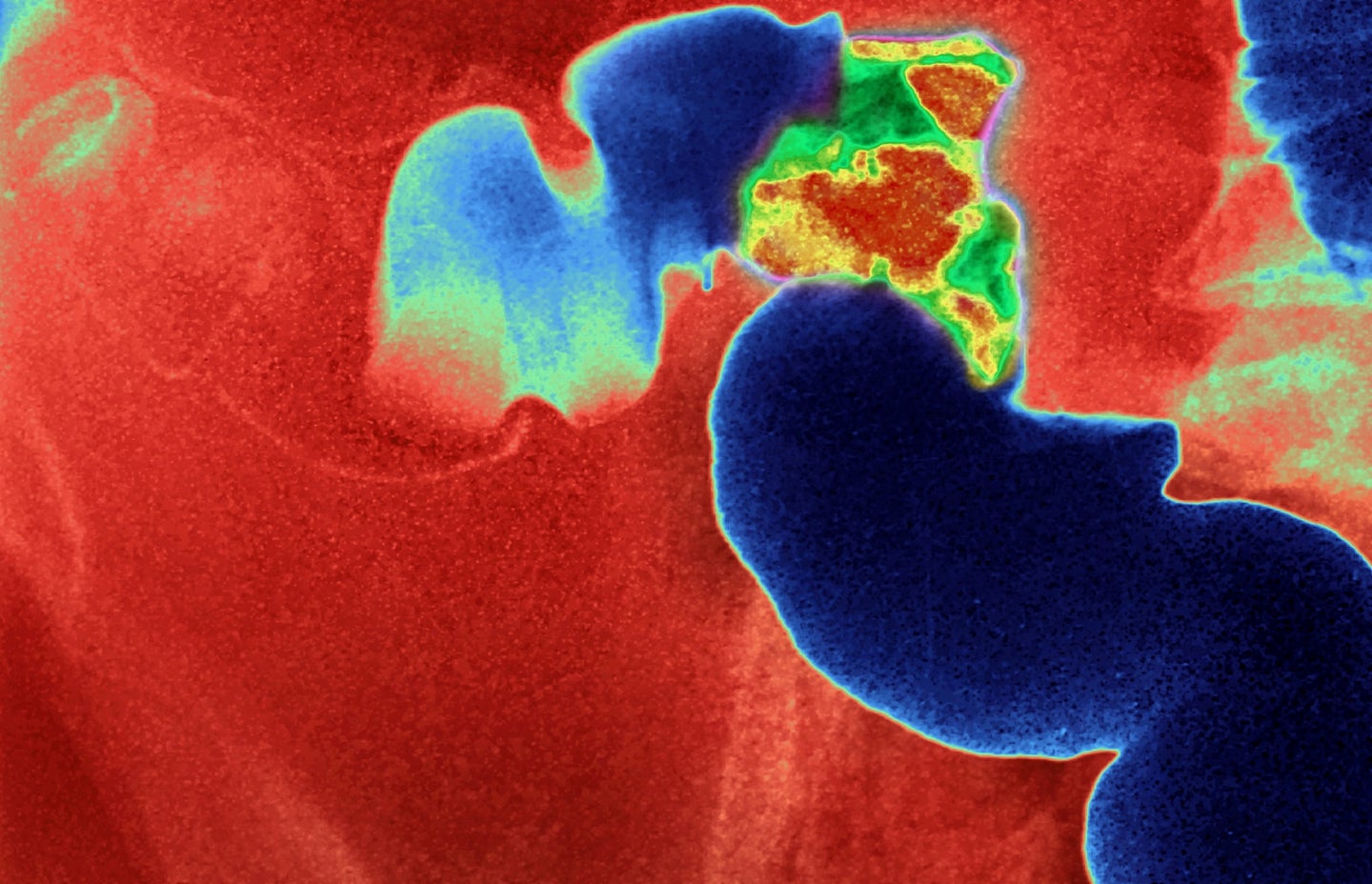

A less invasive method some oncologists are turning to virtual colonoscopies. The procedure uses CT scans to create images of your large intestine to look for ulcers, polyps, and tumors.

[Related: First study of cancer-detecting blood test shows hopeful results]

There is ongoing research looking to improve screening results using a combination of these methods. Some involve using a person’s gut microbiome composition to identify the loss of certain “good” bacteria to predict their risk of precancerous tumors. Others include a multi-step screening process that still includes the recommended colonoscopy. A study from last spring suggests getting a colonoscopy after an at-home stool test; those who did not follow up were twice as likely to die from colorectal cancer.

“We have an opportunity to prevent some cancers from happening by doing the screenings,” says Gupta. “When people are diagnosed early, it’s more treatable.”