Doctors recorded brainwaves to finally ‘see’ their patients’ chronic pain

In a first, deep brain stimulation was used to measure uncontrollable, long-term pain in four people, opening a door to personalized care in the future.

Everyone has different perceptions of pain. Some can sit for hours getting tattooed for an arm sleeve, while others squirm at having their finger pricked. Because pain is subjective, doctors have a hard time evaluating and treating patients who are dealing with it chronically.

Now, neurologists have successfully used a person’s brain signals to predict how much pain they were feeling. The small but unprecedented study, published today in the journal Nature Neuroscience, identified hard clues in brainwaves that could objectively measure the intensity of chronic pain versus acute pain.

The findings are part of a larger clinical trial aimed at creating a personalized brain stimulation therapy that could bring relief to the 51.6 million Americans living with chronic pain. Another recent study in the journal JAMA Network Open reported that the rate of chronic pain in the US was as high as other common health issues like diabetes, depression, and high blood pressure.

“For the first time, the authors were able to understand and visualize the differences between the acute and chronic pain experience on a neural level,” says Akanksha Sharma, a neurologist at the Pacific Neuroscience Institute in California who was not involved in the research. “This is novel and important, learning how and where our brain perceives and processes acute and chronic pain and understanding how the individual brain rewires in response to chronic pain.”

[Related: Medical startup put useless plastic implants in chronic pain patients, says FBI]

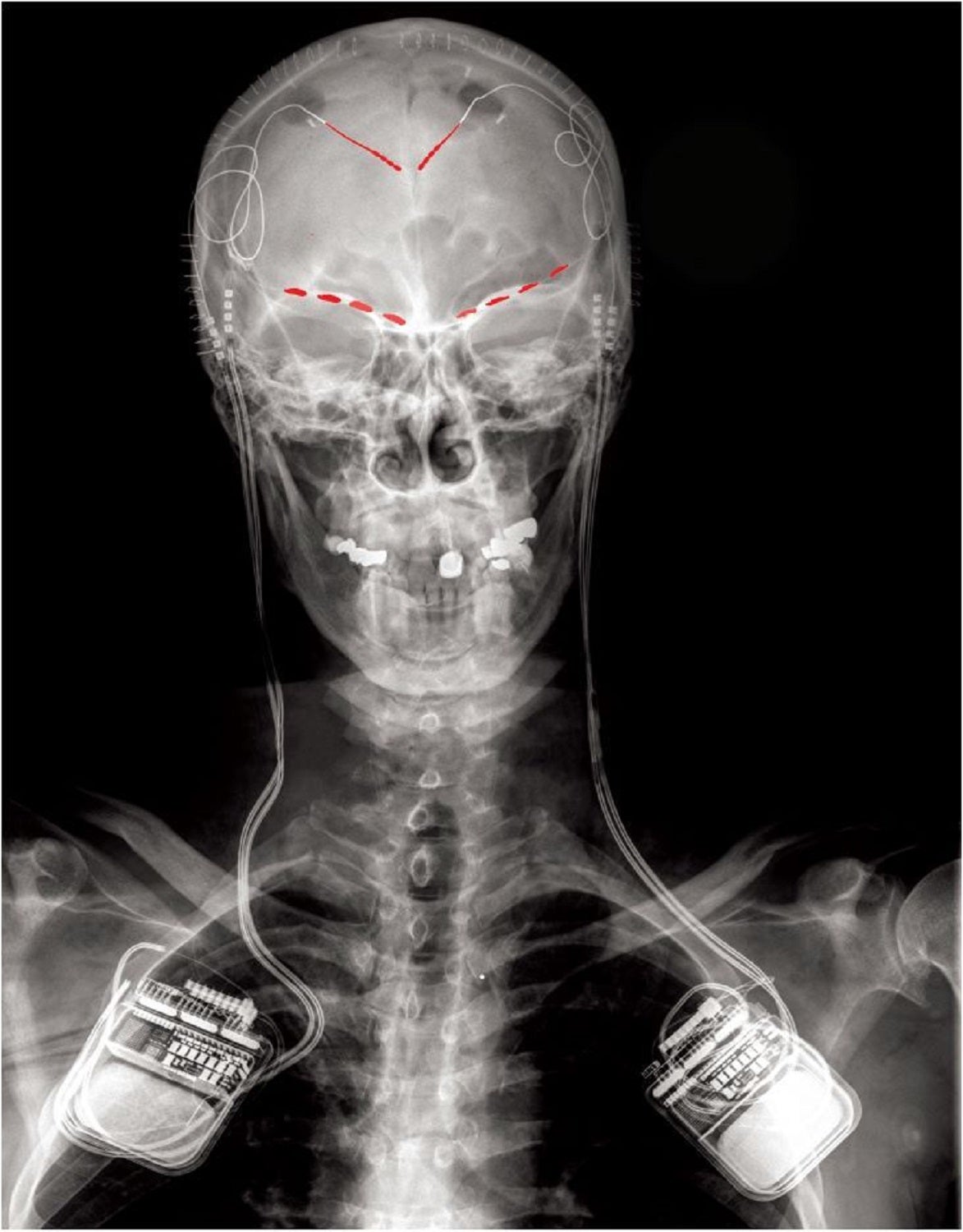

The study authors invited four people with uncontrollable long-term pain—three recovering from strokes and one with phantom limb syndrome—to get implants that tracked neural activity. The patients had exhausted all their treatment options. “They tried medications, injections, and nothing was working. Brain surgery was the last resort,” says lead author Prasad Shirvalkar, a neurologist and pain medicine specialist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Each participant underwent deep brain stimulation, a medical procedure that acts like a pacemaker for the cerebrum. The medical team implanted electrodes in specific areas to detect and record electrical activity from two brain regions associated with pain: the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex. The technique is commonly used for neurological conditions such as epilepsy and Parkinson’s, but has never been tested with chronic pain.

For three to six months, the participants answered surveys about the severity and quality of their pain. Immediately after, they pressed a remote to let the electrode implants take a snapshot of their brain activity. A computer then used the recordings and survey responses to build models that calculated a pain severity score for each patient. Changes in the orbitofrontal cortex helped inform the personalized neural signatures more than any other brain region.

“This information can help drive more customized treatment options for patients,” Sharma says. “If we can objectively “see” the pain experience of a patient, then we can potentially modulate those areas of the brain with new interventions to alleviate or change the perception of pain.”

Brain activity recordings also showed a difference between chronic and acute pain. Signs of chronic pain were more strongly associated with changes in how neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex fired. According to Shirvalkar, this brain region is understudied in its role in shaping the pain experience. The anterior cingulate cortex, on the other hand, is better known for its role in perceiving and processing pain across the body. This brain region was found to be more associated with acute pain.

The team learned that they couldn’t apply the same kinds of brain activity used to chart acute pain in therapeutic research to chronic pain in the real world. “Chronic pain is not a more enduring version of acute pain—it’s fundamentally different in the brain with different circuits,” Shirvalkar explains.

Understanding the differences in how patients are neurologically wired for acute versus chronic pain can help further personalized brain stimulation therapies for the most severe forms of discomfort. Medhat Mikhael, a pain management specialist at the MemorialCare Orange Coast Medical Center in California who did not contribute to the research, says this would help treat the most difficult of chronic pain cases, especially those stemming from a stroke and traumatic brain injury.

[Related: The slow, but promising progress of electrode therapy for paralysis]

While Sharma finds the work fascinating, she warns people to exercise caution in interpreting the data and generalizing it to all neuropathic pain conditions, given that there were only four people in the trial. The study authors say their next goal is to recruit six patients and then move on to a phase two trial where the sample size would increase to 20 or 30 patients. There’s also a risk of life-altering complications with surgical implants in the brain. At the moment, Shirvalkar says noninvasive methods such as electroencephalography and functional MRIs would not be able to record for long periods of time. However, he hopes that one day tech companies can make small wearable devices that track brainwaves.

“Treating pain relies on subjective reporting, or on how the person with pain communicates their pain to their provider. Not everyone’s pain is believed or treated equally,” Kate Nicholson, the executive director and founder of the National Pain Advocacy Center, wrote in an email to PopSci. “For these reasons, the search for phenotypes and objective measures for pain is the search for a holy grail in pain management. Objective measures [like the ones found through this study], if valid and validated, hold promise to transform pain’s assessment and treatment.”