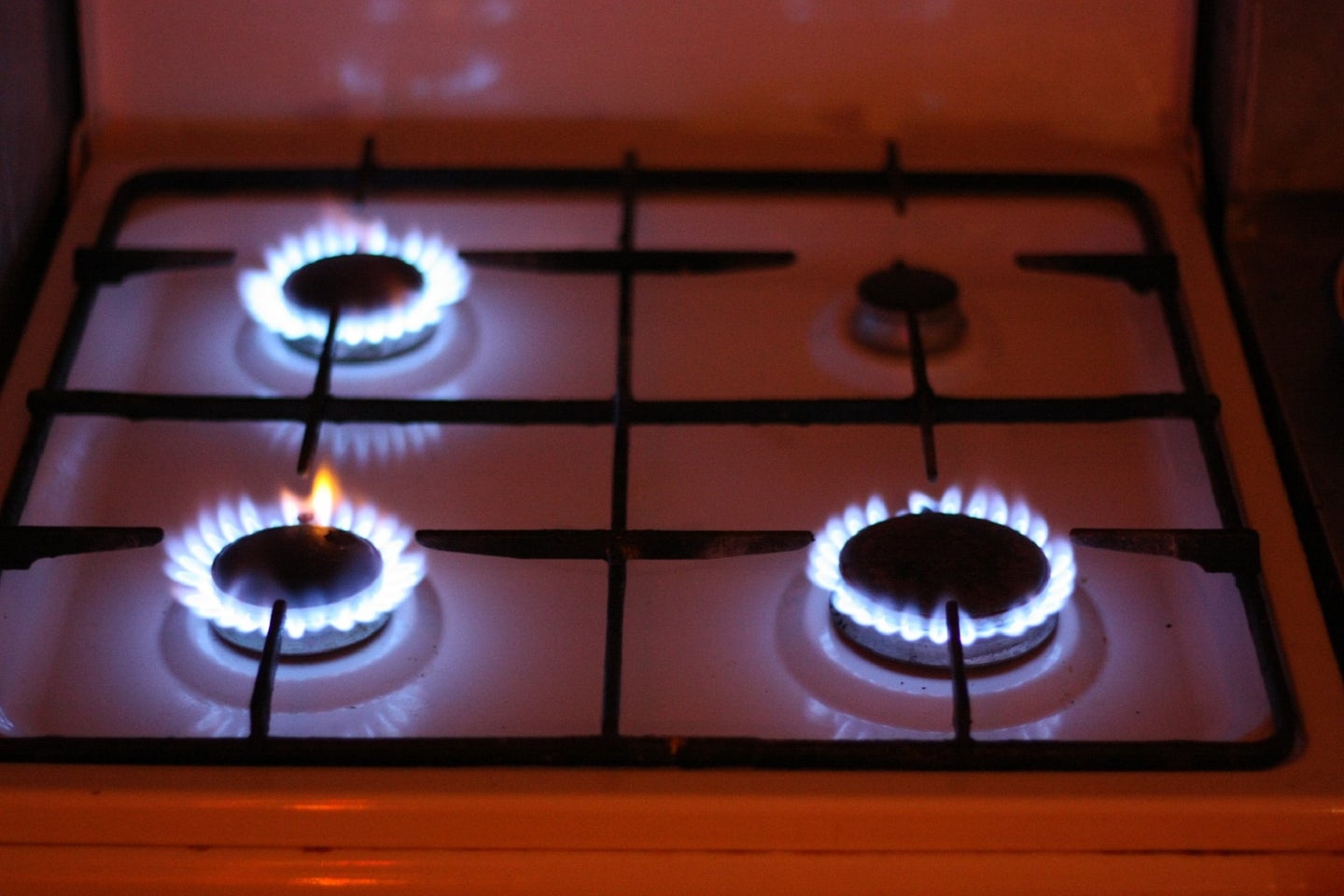

Your gas stove could be hurting everyone around you

A new report has found that stoves are constantly emitting fumes—warming the planet and endangering your health.

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Danielle Renwick is editor of Nexus Media News, where she oversees news features, journalism projects, and media partnerships. This story originally featured on Nexus Media News, a nonprofit climate change news service.

If you have a gas stove, there’s a good chance it’s leaking right now.

A new report out of Stanford this week found gas stoves old and new are constantly emitting methane, the potent main component in natural gas, and that those leaks—from 40 million gas stoves used across the country—have a climate impact comparable to adding half a million gas-powered cars to the roads.

“The mere existence of the stoves is really what’s driving those methane emissions,” said Eric Lebel, a research scientist with PSE Healthy Energy and the report’s lead author. “We found that over three-quarters of the methane emissions from stoves are emitted while the stove is off. So these little tiny leaks from the stoves, they really do add up.”

The leaks Lebel and his colleagues observed were not significant enough to cause explosions (although there were 284 “significant” gas pipeline incidents in 2020, resulting in 15 deaths and over $300 million in damages), but they are part of the reason the burning of fossil fuels for heating and cooking account for about 10 percent of US carbon emissions.

The study builds on a growing body of research showing that gas stoves, used in one-third of US households, do not only contribute to climate change — but also expose millions of people to harmful pollutants that are linked to respiratory illnesses, including asthma, and cardiovascular disease.

The Stanford researchers discovered that nitrogen dioxide, which is produced every time you light your stove, builds up more quickly than previously understood.

“The NOx [nitrogen oxides] and pollutants formed by the flames begin [accumulating] instantly,” says Rob Jackson, a professor at Stanford University and one of the report’s co-authors. “As soon as the burners [are] turned on, the stove starts to give off these pollutants into the air that we breathe.” He says that in many cases, indoor air pollution surpassed recommended limits put forth by the World Health Organization within minutes.

A 2020 paper from the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) documented that homes with gas stoves have about 50 to 400 percent higher nitrogen dioxide levels, 30 times more carbon monoxide, and twice as much PM2.5 as homes without them.

“The problem is that most of these pollutants are invisible, and we don’t have benchmarks or guidelines [for indoor air pollution], so we’re basically putting products into our homes that could be hurting us,” says Brady Seals, the RMI report’s lead author. The EPA publishes guidelines for outdoor air quality but not for pollution inside people’s homes. The WHO released new, more stringent air pollution guidelines in September 2021.

“If we took the World Health Organization’s new guidelines for nitrogen dioxide and said, ‘Any homes that are built today would have to meet these,’ I don’t think you could build a home with a gas stove, based on the numbers I’ve seen,” Seals said.

Children in homes with gas stoves were 42 percent more likely to experience symptoms associated with asthma, according to a 2013 meta-analysis, and 24 percent more likely to be diagnosed with lifetime asthma.

“We know that these gas appliances, and gas stoves in particular, are terrible for health,” says Lisa Patel, a pediatrician at Stanford University. “Higher levels of nitrogen dioxide place children, in particular, at risk for asthma. Carbon monoxide, which can reach dangerous levels, can be a real risk factor for people with cardiovascular disease. And chronic exposure to PM 2.5 increases your risk for a shorter lifespan, for asthma, for decreased lung function and for premature birth.”

Patel said that hoods provide some protection, but according to one California survey, only 35 percent of households use them. “Most people either don’t have hoods, don’t use their hoods, or their filters haven’t been cleaned and they’re ineffectual,” she said.

Lower-income and Black and Indigenous populations suffer from asthma at higher rates than the general population because they are more likely to live in areas with high levels of outdoor air pollution. There is less research into how indoor pollution affects vulnerable populations, but researchers say smaller homes and larger households may increase the risk of exposure.

The Stanford researchers examined indoor air pollution in 53 homes in California; the study looked at 18 different brands of stoves, ranging in age from three to 30 years. They found that new stoves emitted just as much methane and NOx as the old ones.

This study comes as cities across the country are moving to ban new gas hookups in new constructions. In December, New York City became the largest city to pass a ban on gas appliances in new construction (the first of the regulations will take effect next year), joining the ranks of dozens of smaller cities, including Berkeley and Sacramento in California, and Brookline, Massachusetts that have instituted similar measures.

The gas industry and Republican-controlled state legislatures are fighting back: 20 states, including Florida, Pennsylvania, and Texas, have preemptively passed laws that would prevent cities from banning gas in new appliances.

Because so many of the debates over gas utilities are playing out at the local level, Jackson, one of the Stanford researchers, plans to conduct similar research in other states across the US. He hopes that localized data will help build the case for state and local governments to electrify new buildings and retrofit old ones.

Lebel, the study’s lead researcher, said he hopes his work will chip away at the myth of gas being “clean” energy and will encourage consumers and governments to look for truly cleaner energy sources. “We’re burning gas because we say it’s cleaner [than coal], but there are better options,” he said. “We know that and we can say that these [non-fossil fuel alternatives] are better for the climate. It’s better for safety. it’s better for your health.”